As Sebastian Ingrosso steps into the DJ booth for his July 5 headlining set at Light, Las Vegas’ newest dance-music mega-club, it’s a wonder anyone in the Friday night crowd is even looking at him.

For the two hours preceding the Grammy-winning, erstwhile Swedish House Mafia member’s turn on the decks, the 38,000-square-foot, Cirque du Soleil-partnered nightclub at the Mandalay Bay hotel/casino has transformed into a Day-Glo wonderland where dancers, stilt walkers, and other performers roam the crowd in costumes that put Lady Gaga to shame, while the undulating lights, acrobats, and LED screens transform the venue’s ceiling into a dynamic inverted landscape of limbs and strobes.

As Ingrosso begins to twist and tug at his mixer in frenetic, full-bodied fashion, the 318 screens arcing up from behind him and onto the ceiling respond in real time to the music: 3D graphics blend with live camera shots of the crowd as two aerialists drop down from up above. They writhe and flip in response to the sonic onslaught while thermal scanners transform the LED screens into rippling leopard-spot patterns, which moments later dissolves into a sizzling block of red as the DJ cues the crowd.

“I’m living on such sweet nothing!” his fans yell, echoing the refrain of Ingrosso’s mix of Calvin Harris‘ ubiquitous hit.

The automated bells-and-whistles performance may lend credence to critics who deride dance DJs and their shows as the work of soulless button-pushers, but Light, as is the increasing EDM norm, is actually powered by an entire ecosystem of technology and personnel, with a set of immersive tableaux tailored to suit the club’s visiting DJs, a group that also includes fellow SHM member Axwell, Skrillex, and on-the-rise trio Krewella.

Ingrosso brings up the volume, teasing the partiers with a prolonged crescendo as motion sensors detect the increased vibrations on the dance floor, prompting wisps of fog to curl from cannons flanking the stage. When the DJ finally brings the song to its climax, blasts of C02 and foam envelop the crowd. The harder they dance, the faster it spreads.

The same could be said for the EDM business itself, which continues to boom. According to a 2012 EMI study of more than one million consumers, an estimated 73.8 million Americans consider themselves fans of the music (up nine million from the previous year), and they are still eager to shell out big bucks for entry to nightclubs and admission to the dozens of dance-centric festivals continually that keep sprouting up across the country. Electric Daisy Carnival Las Vegas, thrown by Insomniac Events, has topped itself each year with larger crowds and more expansive artist rosters, engendering a cult-like devotion that saw this year’s three-day edition sell out before the lineup, which would eventually feature the likes of Tiësto and Avicii, was even announced.

The dance-music industry has grown so rapidly in recent years that experts are still crunching (and interpreting) the numbers, but estimates pegged the size of the business as a whole at around $4.5 billion for 2012. The money has spawned a multimillion-dollar arms race dedicated to creating the biggest spectacle possible, in the process reaping adoration — and profit — from fans.

These expensive and increasingly lucrative endeavors have grown into a fiercely competitive industry. Last year, Vegas’ ten or so EDM-centric nightclubs are estimated to have grossed a combined $700 million, and fans are spending upwards of $100 million during a weekend at EDC. Genre stars like Tiësto and Deadmau5 make more than $20 million in a year between gigs, tours, and sponsorships, a number that’s only growing thanks to new Las Vegas residencies rumored to be worth that much on their own. As with any booming business, EDM has attracted those with an interest in the bottom line and the sub-bass. The ability of the two to co-exist will likely determine the future of the music’s staging, presentation, and ultimate direction.

But while that relationship evolves, the show — in ever more elaborate and high-priced fashion — goes on.

It’s late June, and we’re approaching midnight on the Saturday of Electric Daisy Carnival 2013 when former Disney CEO Michael Eisner walks into the vast central staging area that serves as a hub for the festival grounds at the Las Vegas Motor Speedway. The 71-year-old current head of the entertainment investment firm Tornante may seem out of place among the go-go dancers and stilt-walkers, but his presence is indicative of an ongoing flirtation between corporate interests and a music subculture that has rushed rapidly into the mainstream.

As rock was to the ’60s and disco to the ’70s, EDM has emerged as a nexus of culture and technology unique to its generation, as enamored with social media and community as it is with a 4/4 beat. A recent study conducted by ticketing site Eventbrite found that EDM devotees are twice as likely as other music fans to want to attend an event when their friends post about it on social media, and are significantly more likely to share via social media throughout an event than are fans of other genres.

In 2012, Nielsen Soundscan named “Dance/Electronic” the fastest-growing mainstream music genre in the U.S., with digital track sales up 36 percent, triple the figure for pop, rock, hip-hop, or country.

“Is there going to be a point where it peaks? I don’t see it that way,” says veteran dance-music promoter James “Disco Donnie” Estopinal Jr. “It’s a cultural thing now. I see my kids listening to dance music. That would have never happened 10 years ago. It’s going to be part of their lives.”

Disco Donnie’s optimism is both understandable and illustrative. After spending two decades hustling as a promoter in underground rave scenes throughout the Southeast and Midwest, the man finally found some interested suitors: In 2012, he sold his company, Disco Donnie Presents, to media mogul Robert F.X. Sillerman for a reported $9 million. The deal marked the first acquisition of Sillerman’s re-launched SFX Entertainment, which launched a buying spree in his billion-dollar quest to build a dance-music empire.

“It is less a question of when I realized that electronic music is so much more than just a genre and more of why did it take me so long to realize the significance and appeal of EMC [electronic music culture],” Sillerman says of his return to the entertainment industry. (In it’s original incarnation, SFX was sold to Clear Channel in 2000 for $4.4 billion — a move that gave rise to the formation of Live Nation.) “Today’s aware and curious generation want and need ways to connect and express themselves. They are the new program directors and A&R executives. This is their creation made by them, for them, to be enjoined collectively. EMC is the fuel for their passion and conscience.”

Last month, SFX filed with the Securities and Exchange Commission, seeking to raise $175 million in an initial public offering. If and when SFX goes public, the move will serve as a litmus test for the industry’s potential value, while also helping to determine how aligned the interests of Wall Street are with those of EDM’s fanbase. Or, to put it another way, the growing involvement of the likes of Live Nation, AEG, and SFX have allowed events to reach broader audiences, but it’s also raised concerns about whether these investments are puffing up the industry to its bursting point.

“I hope it doesn’t get any bigger, because if it gets any bigger, it would be awful to start reporting its decline instead of managing its peak,” says Amy Thomson, the former Swedish House Mafia manager who is now director of music and marketing for Light, as well as an industry consultant. “I don’t think it’s gonna die, no, but I don’t think it’s gonna grow at this pace. There will be a shake-up in the old school tradition of who rules this business, and that’s maybe great. We’ll see.”

Deep in the San Fernando Valley, in a two-story stucco warehouse sandwiched between a floor-tile manufacturer and a nail-polish warehouse, the sausage of the EDM phantasmagoria is made at V Squared Labs, the production company owned by visual-effects pioneer Vello Virkhaus. His advances in multimedia content production, such as video-projection mapping, audio-reactive visuals, and live video mixing, have made him one of the most sought-after creatives in the EDM industry.

Six months ago, V Squared upgraded to these spacious 4,000-square-foot offices. Photos depicting some of the company’s greatest hits adorn the tangerine-colored cinderblock walls: There’s the chameleonic video mapping of Amon Tobin’s groundbreaking ISAM tour; the immersive, projection-mapped vortex of Datsik‘s Firepower run; Skrillex’s audio-reactive, hive-like Mothership set; and stages from the Miami-born, internationally expanded, EDM-centric Ultra Music Festival interspersed with shots of the Red Hot Chili Peppers, the Police, and Bon Jovi, from back when rock used to pay more of V Squared’s bills. (And when they had a smaller office.)

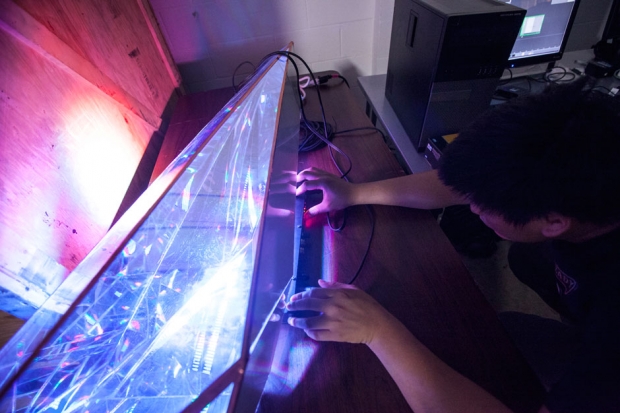

In a converted concrete loading dock behind the main work space, lead programmer Max Chang sits hunched in front of dual flat screens, adjusting sliders and pushing buttons on an indecipherable array of graphs and dials far more mind-boggling than any DJ’s mixing board. To Chang’s left, a series of wires runs from the computer to an LED panel inside of a three-foot-long crystal made of two-way mirrors, a to-scale prototype of the set for Krewella’s upcoming tour.

“If you write the right software, you can completely envelope someone in video,” Chang says of their custom data-building program, Epic, which is exactly what he’s trying to do as he engineers the LED panels to play custom graphic content in sync with the DJs’ live-mixing and lighting. “It’s like its own band up there, in the control booth, the lighting guy and the VJ bouncing off of each other.” The gig is as much instinct as anything. “You’ve gotta know when to black it and then bring it back, as much as you’ve gotta know the tech stuff. It’s all part of the craft.”

That craft is becoming paramount as artists, promoters, and club operators increasingly rely on multimedia content producers like V Squared to help them stand out in a marketplace approaching saturation. Music may be the backbone of the EDM economy, but visual innovation is what drives it — a task that depends on enhancing and expanding the experience of EDM, which gives fans a reason to keep buying tickets.

In the crowded EDM marketplace, “How do you tell the difference between DJ X and DJ Y?” Virkhaus says. “Fifty meters away you can’t tell the difference between Crookers and Dillon Francis, unless he’s got set pieces and a visual identity that becomes him. A unique lighting show, a unique conceptual angle: It’s important. You have these colossal stage structures that are 300 meters wide, and filled with video tiles and video displays and lighting and intricate set pieces, and then somewhere in the middle of this gigantic set down there is a DJ. So, yeah, it’s important to have an identity.”

Building that identity does not come cheaply. A firm of V Squared’s size is likely to charge in the hundreds of thousands to design and implement a stage experience. For young acts like Krewella, set to embark on their first headlining tour this fall, the production is no small concern.

“I never want to be someone’s background music,” says DJ/singer Yasmine Yousaf, who performs in the Chicago-based trio alongside her sister, DJ/singer Jahan, and producer Rain Man. On the strength of club hits like “Alive” — which compelled many a fan to rip their shirts off mid-set at this year’s EDC — Krewella are one of the genre’s most buzzed-about live acts. But they’ve still got work to do. Which is why they’re pouring most of their earnings back into production, working closely with V Squared to design a multimedia experience, including multi-tiered performance platforms.

“As a performer, you think about longevity,” Yousaf continues. “You think about lasting in the scene for more than just a year. You don’t want to be a blip in time. A simple DJ set is such a beautiful thing, but to leave an impact on people, you need to make it into a show. I want people to walk away and remember us for the next 10 years.”

Back at V Squared, Virkhaus’ office is neat and undisturbed, full of hard drives and tapes. He hasn’t spent much time here lately, what with EDC Vegas sandwiched between work in Chicago, South Korea, Brazil, and Croatia, where he’ll work his 15th Ultra Music Festival. The travel is a good sign: A decade ago, Virkhaus was preparing for EDC Los Angeles in V Squared’s original office up the street, in the living room of his apartment.

[ooyala code=”tjeHJwdToaW7BnJe_lGNmDua-HkB3r19″ player_id=”8bdb685537af477d8cd5ea1ebd611511″]

Back then, there was no production manager or senior producer, no individual artists with custom shows and touring crews, no 200-plus GBs of content for EDC Vegas to be encoded, loaded, sorted, and integrated according to a given artist’s timeslot on one of seven stages, each fitted with its own set of LED screens. Circa 2003, there were only projectors, stands, cables, and screens stored in a shed in Virkhaus’ backyard, which he and his two staff members would load into vans and drive to San Bernadino’s NOS Events Center, where they’d hang and rig everything themselves.

“We were the lowest person on the totem pole,” Virkhaus says of EDM’s small force of visual artists and tech crews back then.

The same could be said for the entire EDM community. A decade ago, it was still just called “the rave scene” — the redheaded stepchild of music subcultures, associated with glowsticks and burnt-out kids on ecstasy in the ’90s, and openly mocked by chart-toppers like Eminem, who declared, “Nobody listens to techno!” on 2002’s “Without Me.”

“We were below everyone — we were under the punk-rock people,” says Estopinal, whose Disco Donnie Presents now produces more than 1,000 club events, arena shows, and outdoor festivals each year in cities around the world.

As recently as 2006, Estopinal couldn’t afford to put gas in his car. “Every month, every week, I was risking my house, every show,” he says. “I knew it would get big again. I don’t think anybody could have expected it being this big.”

That same year, Daft Punk played Coachella, introducing their now-legendary pyramid show. Until then, the audiovisual element at EDM shows had, for the most part, consisted of little more than projectors and strobe lights. But as the robot-masked French duo took the stage for the night’s headlining set, they kicked things up a notch: From their DJ booth-cum-command center atop an LED-paneled pyramid, they mixed a tight, career-spanning set of songs as perfectly synced visuals responded from every angle of the stage. The result was heart stopping and all-encompassing. Accordingly, the gig was as much a catalyst for the music’s staging as it was for the music itself.

The idea, according to production mastermind Martin Phillips, who helped design the pyramid show, was to apply the arena-sized spectacle of pop tours to EDM.

“I decided that creating a show with a beginning, middle, and end was important — a show with drama,” recalls the 44-year-old, who runs L.A. production studio Bionic League, which has since created shows for the likes of Deadmau5 and Glitch Mob. “Star Wars works for a reason. You blow up the Death Star in the end. If you blew it up in the middle, it would be nowhere near as interesting.

“DJs own their environment,” he continues. “Which by its nature is somewhat random, based on the crowd. Having these elements enhances that dynamic, that relationship.”

“It’s all about entertainment,” says Krewella’s Yousaf, who at 21 is also a member of the new EDM fan generation. “I want people to really see it for what it is. If you want to go see a DJ DJ a set, go to your local deep-house club and see them not use the sync button and play seven hours of whatever music they’re playing.”

Not everyone is convinced that the ubiquity of gobsmacking effects is healthy for the scene. Even an artist like DJ/producer Daedelus, who garnered acclaim for his Archimedes live show, is wary about the emphasis on big-budget production. “We are in a moment where the club has changed,” he says. “All the lighting saved for a dance floor is now facing the audience from the stage. Often a DJ is left an olive in the middle of a huge salad. People still pay this premium for music that is being more and more marginalized. Imagine paying a $40 ticket to stand at a movie theater. This is modern clubbing.”

In just over 10 years, EDC Los Angeles grew from 6,000 people in L.A.’s Shrine Auditorium to 185,000 people crammed into the sprawling Exposition Park. The event’s move to Vegas in 2011 has only furthered the momentum: Over three days that year, 230,000 revelers descended on the city’s Motor Speedway. While this was happening, Vegas nightclubs saw their bottle service-based business model of glamour and exclusivity top out around 2008, opening the door for the more populist EDM market.

By 2012, Vegas megaclubs like Marquee, XS, Surrender, and TAO could boast of booking DJs like Deadmau5, Avicii, and Skrillex, whose residencies packed venues to their multi-thousand-person capacities. As those artists introduced high-tech, experiential live shows, costs for remodeling a nightclub to meet fans’ growing hunger for sensory overload soared into the millions. Compounded with skyrocketing DJ fees, both nightclub operators and event promoters found themselves scrambling to cover expenses, even as they reaped unprecedented levels of gross revenue.

“It’s not good for the health of industry,” says Insomniac co-founder and CEO Pasquale Rotella. “It’s only good for the pockets of certain people: agents, managers, and DJs. But most are not doing it because they’re in love with the culture. It’s because it’s their job. Vegas coming in and spending this money on the industry throws things out of whack. When you’re an agent or DJ, and you have a booking that is for so much money over here, you have hopes to get that kind of money elsewhere, or at least close to it.”

With new clubs like Light and the reported $100-million behemoth Hakkasan raising the bar for both show production and bank-breaking DJ contracts, Rotella and others say that Vegas is going to have to start capping paychecks or simply refusing bookings in order to balance the scales. One prominent club operator laments that at his spot, they can’t afford to rebook 80 percent of their current acts next year. Despite the cash flow, breaking even isn’t a guarantee, and a DJ’s name is not enough to keep fans hooked.

“It’s kind of like Pandora’s Box: Now they can’t close it,”says industry veteran Steve Lieberman, whose SJ Lighting company works with EDM nightclubs and events like EDC, Ultra, Marquee, and Sound. “Unfortunately, when you see a DJ get paid a quarter of a million for two hours, is he really generating that much revenue? Does ‘Levels’ sound that much better when Avicii plays it or when DJ Vice plays it?”

But there are expectations to consider. “We’re always under pressure to produce something spectacular,” Lieberman adds. “When you go in and spend $15 on a drink, you want to know [the club] has a $400,000 video wall.”

For an industry whose success is based on building and maintaining links with fans, the question remains whether the increasing presence of lawyers, corporate investments, and billion-dollar buyouts will undermine EDM’s egalitarian ethos of peace, love, unity, and respect — or, as fans call it, PLUR.

In its IPO filing, SFX went so far as to change its name from an “Electronic Dance Music” company to an “Electronic Music Culture” (EMC) powerhouse whose acquisitions include not only promoters like Disco Donnie Presents and European powerhouse ID&T, but community portals like digital-music outpost Beatport and paintball party Life in Color.

“It’s uncharted territory,” says SFX Head of Acquisitions Shelly Finkel. “It’s a work in progress. There’s a new generation coming up. I was in an airport yesterday, and I got to talking to this kid, he must’ve been about 14. I mentioned we’re doing Tomorrowland [another EDM mega-festival], and he says, ‘I know, but I’m too young to go. I can’t wait till I’m old enough.’ So if that’s true, that’s four years from now, and a group of kids who couldn’t go before will be going.”

Proponents say the involvement of a company like SFX will help protect and strengthen EDM by forging relationships between its manifold players — the producers, the promoters, the venues — and by providing a base of capital for creative endeavors that were once prohibitively expensive. Moreover, Sillerman’s focus on buying up small- to mid-sized regional promoters could mean a safe bet on a segment of the industry that’s likely to maintain its level of success, even if the mainstream popularity of EDM wanes. (Neither Finkel nor Sillerman could comment directly on their business, due to an SEC-mandated quiet period following the IPO filing.)

Others are wary. “That company is about Wall Street and not about music and art,” scoffs Rotella, adding that he rejected a recent SFX offer to partner up. “My actions can tell you my confidence about that.”

That’s not to say he’s completely averse to corporate investment. At June’s EDMbiz conference in Las Vegas, Rotella confirmed rumors that Live Nation would be purchasing a 50 percent stake in Insomniac. Dubbing it a “creative partnership,” Rotella says he and his team are getting the best of both worlds: bolstering Insomniac with Live Nation’s capital and infrastructure, while retaining creative control. This is at least a slightly ironic turn of events for Rotella, who in mid-July had a civil suit against him alleging unfair business practices dismissed. It wasn’t that long ago that Electric Daisy was throwing elbows. Now its trying to sound the voice of reason.

“Look around: There’s not any Live Nation people here,” Insomanic creative director Bunny Eachon points out backstage at EDC. “Zero. Any company that would get rid of us to hire suits would be stupid. Now we just have access to money to make these dreams happen, instead of having to worry about, ‘Oh shit, if we don’t make money on this, we are bankrupt.’ I am excited for the future.”

The support from Live Nation will allow EDC Vegas to upgrade more of its LED-lined stages to full-on sets like the Alice in Wonderland-esque tableau of this year’s Kinetic Field main stage, as well as to expand EDC into new locations, as with this month’s event in London’s Queen Elizabeth Olympic Park. Eachon says there may even be a feature film in the works, based on one of the Insomniac Events trailers he directed.

“Disney, they did movies and made it a theme park,” he says. “We are creating a theme park and making movies from the theme. It’s going the other direction.”

At this point, the consolidation and monetization of electronic music culture is inevitable. Industry powers like UMF and Ultra Music, former rivals once vocal about maintaining their independence, partnered last year. And veteran insiders like Thomson have been vocal about what she calls “investment buzzards” circling EMC.

“The number of investments coming toward it scare me,” she says. “Because buying into it inevitably means that you believe that it’ll multiply. And if you’re buying into it and think it’s a five-times multiple, then you’re wrong. If the production increases, the tickets increase, and it’s a very fine balance between those two things that people have to be careful about.” She’s also careful to note that “ultimately, this is about the fans.”

On the edge of a neon lily pad by EDC 2013’s Hard Stage, two girls slip out of their homemade butterfly wings and stretch out on the grass near the lip of the stage. The Kansas City natives are exhausted from their first Electric Daisy Carnival, and wary about the prospect of a long drive home the next day. But when asked about their favorite sets, their glitter-rimmed eyes light up: Krewella. Datsik. Yes, definitely Datsik — the energy, the visuals, the PLUR.

“You’re completely inside of it,” raves Christy, 21.

The girls say they’ve been wanting to come to EDC for the past few years, and worked overtime for nine months at their waitressing gigs to save up the roughly $1,000 they’ve spent on tickets, travel, costumes, food, and merchandise.

How much is too much? Would they be willing to spend more to come back some day?

Christy raises her eyebrows. “Everything is so expensive here already,” she says. “But I’d definitely try.”