Dinosaur Jr. by Dinosaur Jr. is the comprehensive oral history of the titular Amherst trio, as told by those who witnessed the band’s birth, breakup, and fruitful reunion. Out now via Rocket 88 Books, the limited-edition text contains exclusive interviews with band members J Mascis, Lou Barlow, and Emmett Jefferson “Murph” Murphy, as well as former mates Mike Johnson and George Berz, and other longtime friends of the beloved alt-rock pioneers.

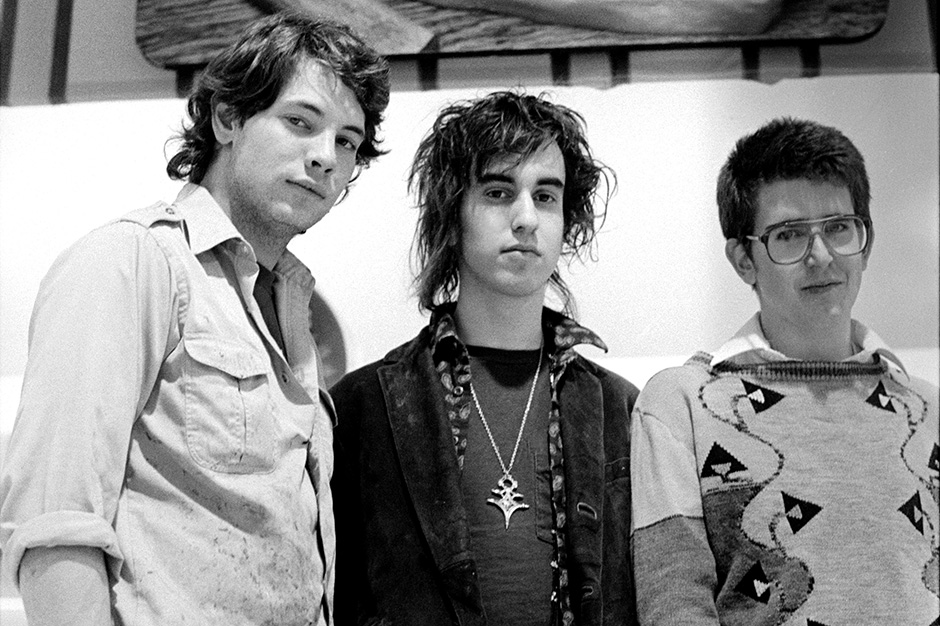

Also featured in the coffee-table-friendly chronicle: rare band flyers, previously unseen photos, original gig contracts, and other visual memorabilia (including a poster from when a certain band of Rock and Roll Hall of Fame inductees opened for Dino). The end result is a raw, but lovingly curated look at 30-plus years of Dinosaur Jr.

SPIN recently spoke with two people involved in the project’s creation: the book’s editor, Russell Beecher, who discussed his longtime devotion to the band; and Murph, who recalled Dinosaur Jr.’s early days and explained why every good band would benefit from such definitive documentation. Read those conversations below, and check out an excerpt from the book.

How did this project first get started?

Russell Beecher (Editor, Rocket 88): When I was a kid, I was an absolutely huge Dinosaur Jr. fan. I grew up loving them. I got the idea for a book and I went and flew out to where they were touring in London. Everything ended up going really well so we figured we’d go for it.

What was it like collaborating with J, Lou, and Murph on this project?

I flew around to do interviews with all of them. I did individual interviews — Lou talks quite a bit, J tends to be more reserved, and Murph chips in his parts. The thing with J is he doesn’t talk much really, but when he speaks everything is important. He doesn’t say much, but everything he says is the truth. He takes it slow, but it’s all true. In the nearly 18 months it took to put the book together, I’d say I spent collectively a couple of weeks with them doing interviews. And it was easy to research. Just being a fan myself for all these years and stuff, I’d already done all the research before. So the rest of the time was getting all those images that hadn’t been seen.

Who provided those unseen images?

We got really lucky because Jon Fetler, he was kind of like a member of the band, he ended up having a lot of old photos from touring. He had a really good eye for photography. Some old pictures can come out really bad because of bad lighting and stuff, but they’re such a great band and I think all those images really bring that to life. There are some taken where they were really young and it just shows the way they are. They’ve always been all about the music.

As a fan yourself, what was your favorite part of the book?

Loads of stuff, really. They sort of went into each chapter they had together, which is something we don’t see from many bands anymore: as kids, all those years touring, the breakup. It was important to see where they were coming from. It was also quite nice getting to meet them. I mean, sitting down with Lou Barlow for a chat and a few drinks. [Laughs.] Plus, they’re quite easy to get along with.

Did you learn anything from just hanging out with the band that maybe isn’t immediately clear in the book?

They work really, really, really hard.

…

What would you say is the most valuable part of this book?

Murph (Drummer, Dinosaur Jr.): It’s so thorough. It really encapsulates the beginning to the current time and it’s a really thorough perspective on the band and how we did it, how we do do it, and how we still keep it going. I was actually really satisfied with it. I think every good band should have something like this. Because at some point you’re just gonna be history, 50 or 100 years from now, and it’s nice to have documentation. I think partly with technology and Facebook and everything else, I’ve noticed this trend, especially with younger bands and kids, they don’t — I think it’s really important to know where you’re from. What town you represent, or where you grew up — because when we were doing music that was such a big part of it. That’s why this famous punk record This Is Boston, Not L.A. was put out, because they were two very different scenes and it was really important to single out which scene you were from. And I’ve noticed a lot of kids, they’ll have a favorite band, and I’ll be like, “Alright, do you know where they’re from?” And they’re just like, “No.” They don’t seem to understand. And so I guess I like the fact that this book helps solidify that and reinforce that importance. I just hope that kids could just look at that and understand that that’s a big part of making music. It’s your lineage.

I definitely agree with you. Today, it seems like what you’re doing in the moment is more important than where you’re coming from as an artist.

I think there’s a trend in music — which is a bummer — because of social media, music has become like fast food. You just want it now. It’s quick, it’s like a drive-through, you get it. There’s no big experience that goes with that. And that’s what I think people are missing. Because when we were doing it, it was all about the experience. I’ve been playing in this project Sunburned Hand of the Man and it’s like a double drumming thing, it’s kind of like an improv. It was started in the ’90s and it has this cool thing about it. It has different members. Wherever you play a gig different people show up and it’s like a collective. So you never really know what’s going to happen. And half the band are guys that are kind of my age — 40s — and the other half are kids who are like 25, 27. So it’s really cool to collaborate together. But we just played a gig at Hampshire College here in Western Massachusets on Friday, and I was just telling some of the guys, when I was giving them a ride, about the history of Hampshire and how its so funny to be coming back here because this is where we got our start, and I could tell they were blown away. They don’t have those stories. It’s weird, like, they’re all in bands, but they don’t really have that story, which is odd to me.

You guys go into some intensive detail about your breakup in the book. Was that difficult?

No, now we just laugh about it. Our dysfunction is pretty known as part of our band, like a lot of bands. It’s always either money or drugs or a woman — like Yoko — or whatever. We were just funny because we were kids. Like, people think we all hang out together, and that’s the odd thing about our band: We were all very different people. We soon realized we could make really good music together, but we didn’t really hang out together, so it created this weird rift and tension because you don’t have a lot to talk about, really. But now we laugh about it.

Do you guys have that same sort of relationship today — different people who come together over music — or have you become closer over the years?

Oh yeah, we’ve become totally closer and we have way more in common. We’re more like brothers today. We’re totally like a family.

When you were first opening up the book, what were the thoughts running through your head seeing it all come together?

It was just a blast from the past. I was really shocked at how thorough it was. I thought it was just going to be this glossy picture book and it was just going to be, like, whatever, and you just kind of skim through it. And I was like, “This is like a real book with a serious beginning and an end. It’s this whole retrospective look at our lives and our band.” It was cool that I wasn’t expecting it. It’s like going somewhere and all your high-school classmates are there — you’re just not ready for it.

What can Dinosaur Jr. fans learn from reading this book that they hadn’t known before?

I guess that our personalities are a lot about the music and not just… like, kids today seem to want to make music just for making music’s sake or because it’s cool or because they can get chicks or they can get famous. And it’s very evident and clear that we did it because we just did it. We liked doing it and it’s just what we could do. We didn’t have a goal. I remember this guy telling me one time — I was in the Lemonheads for a short time and we did a record and toured. I remember talking to one of our guitar players and he’s like, “Oh, come on dude — at one point when you were, like, 14, didn’t you think by playing drums you could get laid?” And I was just like, “No. That’s not it. Drums were cool and I really liked to play drums. I wasn’t thinking about the girls, what are you talking about? I just wanted to play drums, man.”