Release Date: March 09, 2010

Label: Columbia

It now has been three years since the Shins last changed your life. So blessed and cursed by the instant indie ubiquity of the Garden State soundtrack, the band’s last album, 2007’s Wincing the Night Away, shot to No. 2 on the Billboard charts. But all was not well. In 2008, frontman James Mercer effectively fired drummer Jesse Sandoval and keyboardist Marty Crandall, restocking with new sidemen. Amid the controversy, he also announced that the Shins had left their label, Sub Pop, for Mercer’s own start-up, Aural Apothecary. A rumored 2009 album never came.

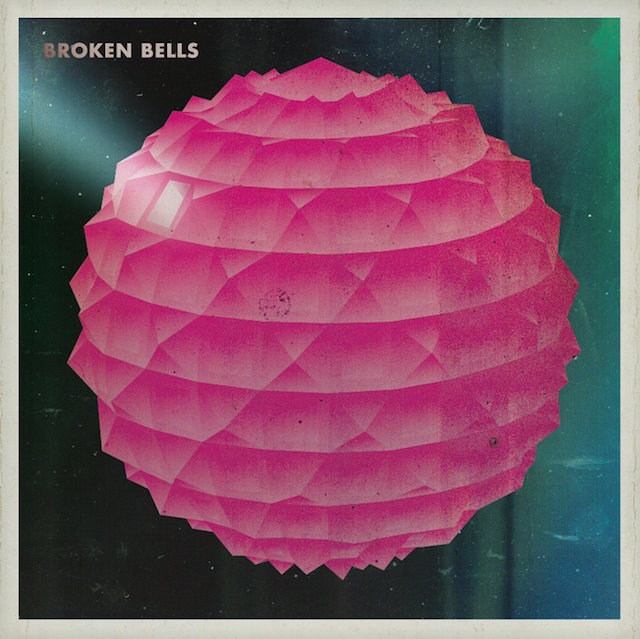

The first musical output from Mercer after Wincing was “Insane Lullaby,” a track off Dark Night of the Soul, the bizarre, ill-fated book/album project assembled by producer Danger Mouse, moody folk rockers Sparklehorse, and filmmaker David Lynch. Now, deepening their collaboration (and filling the Shins-less void), Mercer and DM, a.k.a. Brian Burton, have formed what they insist is a proper new band: Broken Bells.

Mercer, with his delicately expressive voice, and DM, the underground rap beatmaker turned mash-up phenom turned Jack Nitzsche wannabe, seem a natural fit. And sometimes they are. The phantasmagoric “Sailing to Nowhere” perfectly fuses their sensibilities, as Mercer sings gorgeously about “guts on your blouse,” while Burton thrashes about with a Hammond organ and feedback-drenched guitar, building toward an epic orchestral coda. And “Mongrel Heart” is a fascinating refraction of Burton’s obsession with film scores, melding an intrepid spy theme with the dramatic grandeur of a spaghetti western.

But where these songs are a clever juxtaposition of Mercer’s Kewpie-ish falsetto and Burton’s dissonant, clattering production, Broken Bells is mostly a calm and measured experiment. The album seems to want to rewrite the Zombies’ master class in baroque pop-rock, 1968’s Odessey and Oracle. Instead, it veers into pretty, fussed-over easy listening.

Perhaps Mercer’s indelible voice and earnest, opaque lyricism are to blame. Despite the new group, he’s the same guy: gentle, confused, prone to fits of spastic buoyancy. On “The Ghost Inside,” he sings in a breathy, unrecognizable chirp, a trick that only momentarily masks his identity. By verse two, the fog dissipates and your old, familiar friend’s voice is back. But unlike Mercer’s work with the Shins, swooning, memorable choruses are scarce.

Ultimately, though, Broken Bells is Burton’s show and a troubling trend emerges. This is the third time he’s teamed up with an iconoclastic rock vocalist: In 2007, he worked with Damon Albarn in the Good, the Bad & the Queen; and in 2008, he coproduced Beck’s Modern Guilt. All three of these projects emanate a tasteful, bloodless efficiency. The songs appear to take chances — sweeping chord changes, symphonic progressions, darts into electronic sound — but there’s little at stake.

For Broken Bells, Burton and Mercer worked, like a band does, together in the studio. Compare that method to the highest highs of Burton’s other, most successful twosome, Gnarls Barkley. He and Cee-Lo Green, a mischievous, gut-busting singer, completed the magical bits of Gnarls’ debut by e-mailing MP3s back and forth, tweaking while rarely seeing each other in person. Something seemed revolutionary about the distance between the duo, as though they’d created a new creative dynamic — the solemn, hermetic producer splicing the frenetic cries of his muse. Necessity was the mother of their invention. Perhaps Burton, unlike Mercer, needs that isolation and just isn’t cut out for band life.