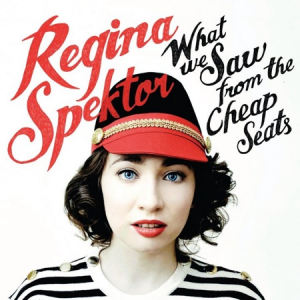

Release Date: May 01, 2012

Label: Sire/WEA

If you’ve heard Regina Spektor’s voice just once, it was probably when she shattered “heart” into polysyllabic laughter on her 2006 single “Fidelity,” and you also probably heard her described as “quirky.” Because nowadays every hint of the eccentric, be it spark of inspiration or precious affectation, is dismissed by the constitutionally tight-assed and cooed over by connoisseurs of cute as “quirky.” Some drama-club reject’s twee desecration of rap hits? Quirky. Querying Siri about tomato-soup delivery? Quirky. A classically trained oddball bashing the conservatory out of her system with bratty anti-folk piano rambles, ramming the girlish curl of her vowels into glottal roadblocks? You know it.

Granted, by the time of Spektor’s 2009 album, Far, her caprices had turned willful (on “The Calculation,” she constructed a computer out of “macaroni pieces”) or sententious (drag and drop “Laughing With” beneath Lily Allen’s “Him” or Joan Osborne’s “One of Us,” on an unbearable Spotify playlist of dim songs about the divine). They even tainted a breezily self-accepting quip like “I’ve got a perfect body / Because my eyelashes catch my sweat” with guilt by association. And it was dispiriting to hear a songwriter who clearly adored classical music more for its melodies than its classy aura or structural intricacy repeatedly drift off on a sea of undifferentiated arpeggios and ostinatos.

But on What We Saw From the Cheap Seats — recorded in California with producer Mike Elizondo, the onetime Dr. Dre assistant who streamlined Fiona Apple’s Extraordinary Machine — Spektor’s idiosyncrasies fit her as loosely and comfortably as her grandpa’s cardigan. Yearning opener “Small Town Moon” is an exercise in empathy, wherein the daughter of Jewish immigrants who traded the soon-to-be-former Soviet Union for New York mid-Perestroika inhabits the hopes and fears of what sounds like a middle-American dreamer, obsessing over the question, “How can I leave without hurting everyone that made me?”

More importantly, the chorus of “Small Town Moon” — “Today we’re younger than we’re ever gonna be” — showcases Spektor’s gift for investing platitudes with enough gusto for them to ring out anew. The 32-year-old has grown deeper into a role that becomes her: the chin-up elder sister to an avid cult, offering non-frivolous advice on adjusting to life in a world with little patience for your adorable crochets. A line like, “Love what you have and you’ll have more love,” may not offer a wholly unique sentiment, true. But it suggests a worthwhile experiment regardless.

Never precious about a pain she never denies, Spektor employs vocal whims as distractions from everyday sadness, the slightness of her improvisations implicitly accepting the impermanence of all emotional states. Whether she’s lippily imitating a trumpet flourish at the close of “Party” or translating the horn riff from “Low Rider” into a “doo-doo-doo” coda on “Patron Saint,” her flourishes complete her songs. The most arresting moments on the intended showstopper “How” (as in, “Can I forget your love?”) are Spektor’s creeping left-hand piano fill and a series of interjected mid-line oohs that would sound normal double-tracked or relegated to backup gals, but instead catch your ear up short. Without those touches, “How” is a winning exercise in soul-pop songcraft. With them, it’s a rewarding display of self-expression from a self well worth expressing.

Then again, if you’re listening for something to hate, maybe your blood pressure will rise to “Oh Marcello,” its vocal an exercise in vaudevillian Eye-talian, its music a choppily phased electric piano, its chorus an inexplicable veer into the Animals’ “Don’t Let Me Be Misunderstood.” Or maybe “Ballad of a Politician,” a rather simplistic study in whoring for power, will slide the bamboo under your fingernails. But the make-or-break performance here is “All the Rowboats,” in which masterpieces of fine art dream melodramatically of escaping from the museum where they “serve maximum sentences…for being timeless.” Spektor reserves her deepest pity for the poor glass-encased violins wasting uselessly away. Then she imitates drum-machine blasts. Deal with it.

Sure, the tightasses have a point. To be quirky in 2012 is, as often as not, a strategy to disguise one’s brand identity as a sensibility, to adopt a playful appearance while denying the spontaneous delights of true playfulness. But you know, a quirk used to be a good thing, the sort of unique, often endearing fillip of personality that marked an individual as worth knowing better. Regina Spektor offers up loads of those, and she makes good on them.