“When I listen to my early songs, it’s a sort of uncomfortable experience,” Nick Lowe says in the hotel lobby on a bright August afternoon in lower Manhattan, with the staid expression of a doctor proffering a bleak diagnosis.

“I always think ‘Oh man, why did you do that? Why did you do it twice?’” He smiles, a boyish glint peaks through his Buddy Holly-style frames. His marshmallow-white teeth match his full head of tidily combed hair. “They’ve got this youthful enthusiasm and zeal about them, which gets on my nerves.”

In Lowe’s line of work (pop music), musicians take great pains to obscure their age and maintain their youthful identities as long as possible. As a younger artist facing a career nadir, Lowe took the opposite approach. In his mid-30s, the tender-voiced singer threw in the towel on chasing youth and went full fogey. “I thought, if you could come up with a way of presenting and writing for yourself which would make it an advantage to be getting older — not something to hide — then people would envy your wealth of experience,” Lowe said on a podcast with The Hold Steady’s Craig Finn.

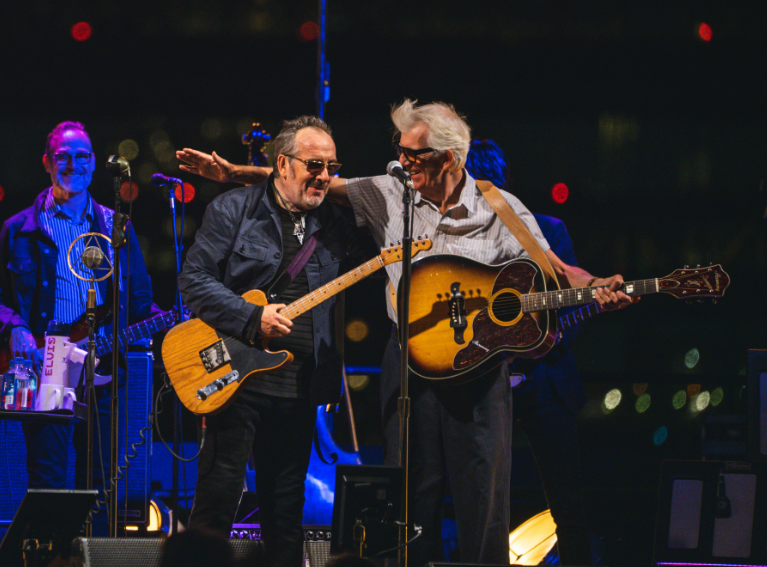

At 74, Lowe is finally the appropriate age for his brand — and the brand is booming. Since COVID-19 restrictions were lifted in 2021, Lowe has done three tours across North America, the U.K. and Europe backed by Los Straitjackets, the feverish surf-rock band who don Luchador masks onstage. On May 14, he will up that to four with summer tour dates opening for his friend and faithful hype-man, Elvis Costello, for whom Lowe produced his first five albums.

Lowe’s fan base also isn’t what you might expect. Earlier that week, Lowe gave a barn-burner of a show at TV Eye, a tiny dive venue deep in industrial Queens. The floor was jam-packed with attentive hipsters and beefy, metal-looking guys in the front row. There wasn’t a whiff of nostalgia since most of the audience wasn’t even born during Lowe’s commercial peak — 1979’s chart-topper “Cruel to Be Kind.” When Lowe reappeared alone for a second encore, a stunned silence fell over the room as he strummed a slow, serene rendition of “Alison” — the new wave ballad he produced 45 years earlier.

For the last five decades, the story of Nick Lowe has been the same: You may not know the man, but you know his music. Lowe grew up in Surrey, England in the 1950s, half of a generation behind the Beatles. His earliest bands, Brinsley Schwarz and Rockpile, cultivated London’s pub-rock and rockabilly scenes that would eventually evolve into punk and new wave. Lowe shaped those genres by producing modern classics by The Damned, The Pretenders, Dr. Feelgood, and Elvis Costello’s first five albums. Lowe took whatever leftover studio time he could to record his own solo albums, such as 1978’s pop potpourri, Jesus of Cool.

Today, Lowe hardly considers much from those early solo albums real music, even if people like the songs. In the ’90s, he scaled down and focused on his craft. As critic Robert Christgau indelicately wrote in a review of 1990’s Party of One: “The latest old fart to slip into limbo and come back to play another day, Nick the Knife is a writer again, every song honed and there for a reason.”

Lowe kept honing. His mature 1994 record The Impossible Bird yielded “The Beast in Me,” which Johnny Cash famously covered years after Lowe’s marriage to his step-daughter fell apart. He went even darker on 1998’s blues-inspired Dig My Mood, which SPIN can reveal is getting a 25th anniversary reissue later this year, along with a 10th anniversary reissue of his holiday album Quality Street.

“As I got older, I experienced what it’s like to be lied to and what it’s like to lie to someone,” Lowe says in his thoughtful, understated way. “To have your heart broken.”

SPIN: You’ve been writing about growing older for about 20 to 30 years now. I mean, your record At My Age came out 15 years ago.

Nick Lowe: Really?

There’s a TV interview of you on the BBC from 1990 where you said you never thought you’d be doing music at 40, and that hopefully at 60 you’d be doing your best work. How has your perspective on aging changed since then?

It’s quite a hard one to answer. I think that I did all my thinking about getting older and how it was going to impact me when I first thought of developing a way of producing myself and writing for myself that would use my aging as an advantage. The older I got, I’d grow into it instead of [it feeling] weirder and weirder. I don’t really think about it much at all now. [Pauses.] My voice is going to go. But it hasn’t yet. All my fingers still work. I wake up in the morning and I think old guy things like, “oh man, am I going to be able to actually do this?” As opposed to “how am I going to look, what sort of clothes am I going to wear,” which used to be the fun part.

Have you seen these Rolling Stones documentaries? My Life As A Rolling Stone, where they interview each one of them individually? They talk about getting older in the most relaxed and candid way. And people are still crazy about them. And it’s no mercy clap that they’re getting, or people coming to look at an animal in a zoo. I’m not comparing myself to the Stones, of course, but you never want to feel that people are coming because they feel sorry for you, or that they’re coming out of sort of loyalty. I would really pack it in then.

If we do compare you to the Stones for a moment — I don’t know exactly what their set list is nowadays, but I highly doubt that they play as many new songs as you do. Your set list is mostly newer material. Is that a conscious decision to make yourself feel still relevant and not an old geezer who…

Who’s going through the motions?

Yeah, exactly.

You want to feel like you are relevant and doing a good job without getting down with the kids. Doing something… not humiliating, you know? You’ve gotta be ‘to thine own self true.’

Do you remember when you realized you could actually make a living as a musician?

I was broke for about seven or eight years. I existed on no money at all, but everybody I knew existed with no money at all. I suppose it was when I got my first performing rights check for about £200, which in 1973 or ’74, that was a real lot of money. I remember thinking then “Wait a minute, you might be onto something here.” I was just starting to actually write some songs. I think I’d written “(What’s so Funny ‘Bout) Peace Love & Understanding” then. I’d just started feeling like I could write songs that were my own idea, my own style. Up until then, like everyone else, I was copying my heroes.

On the other side, did you ever think to yourself, “Ah, this might not work anymore?”

Oh yeah. Definitely. [Around age 35 in the mid-’80s,] I realized that I was extremely unhappy. Everything had gone wrong. Domestically, my marriage with Carlene just sort of stopped, really. I didn’t like the records I was making and the songs I was writing. I looked in the mirror and suddenly thought “Man, who is this big fat guy?” I didn’t seem to eat anything and yet I was really fat.

Then I thought “Right, this has got to stop.” I took myself in hand and sort of cut myself off from everything and changed my operation. That’s when I hatched this plan about how I was going to develop a style that would suit me going into the future and to stop trying to do this kind of zany “pop guy” stuff. I couldn’t stand it and the public clearly got tired of it as well. I wanted to play quiet, that was the thing. I thought “To hell with this loud stuff, because if you play loud, you can’t swing.” And whatever I wanted to do, I wanted swing to be part of it.

A big revelation was when Elvis [Costello] encouraged me to do solo shows. I was very reluctant but he said “Honestly, you’ll really enjoy it. Give it a go.” I think I went on tour with him. He knew I needed to do something, so he took me just to play rhythm guitar and sing harmonies with him — and he made me open the show. He said “Why don’t you go and just do a few songs before the show starts? Just five or six.” I did that, and to my astonishment, people really liked it.

But the thing I noticed was that when I played my songs on my own just with a guitar in front of people, that’s when I saw all the flaws in how they were originally written. It became very, very obvious to me. Playing songs solo had a big influence on my plans for the future. I thought “I’m going to devise a new way of writing for myself and it’s going to mean that the songs are really going to work. They’ll be fireproof, absolutely fireproof.” That’s why I never do “I Love the Sound of Breaking Glass,” because there really isn’t a song there.

It’s more of a sound and a feeling.

Yes, exactly. So I thought in order to build the “swinging old man” image I had of myself, the songs have to be absolutely great. That’s when everything came into focus for me, and that would’ve been about ’85 or ’86. I thought that people would catch on to this idea eventually, but I’d have to be patient. Really, to a time like now when I’m, frankly, an old man. I thought that if I could get this right, then it would be cool to be old. And it has worked out.

Up until the lockdowns, you’d basically been on tour since 1968 or something like that. What drives you to play so many live shows? Is it a job that pays the bills? An ongoing passion? A feeling that “I need to do this as much as I can before I can’t anymore?”

A bit of all of those, I suppose. It certainly pays the bills, there’s no doubt about it. Record sales, they’ve just collapsed. I still get royalties from movies and TV things, which happens quite often. Occasionally someone will cover one of my songs. So, I still have a royalty stream coming in. But there’s no doubt that playing live pays the bills [pauses.] But there’s also kind of a fascination with it. To see if you can make it work, if it’ll come forth — this strange thing that happens when the music almost seems to play itself. I don’t want to get too carried away, but there is something mystical that happens [onstage.] Because no one ever thought that anybody old would ever play rock and roll, certainly not in my youth. It wasn’t for old people. But the fact is that the old people can do it pretty well, actually.

It’s an ecstatic feeling when it’s working, but you never quite know why it does. You have to put up with travel — domestic flights in the United States are probably the most excruciatingly awful experience that anyone can put up with. But all that stuff you put up with to see what’s going to happen in the evening.

How did you feel the first time you stepped onstage in two years?

It was a bit nerve-wracking. I thought “Oh God, how do you do this?” Because I always think, like many people who do this for a living, that you are sort of two people. The person that does the shows and the guy who empties the dishwasher and takes the dog for a walk and does the recycling. The domestic guy doesn’t know how to do the shows and the guy who does the shows doesn’t know how to do the recycling, doesn’t have the faintest idea. So transitioning between the two is always a bit of a production. My wife, when I’m about to go on tour and I leave the cooker on or forget to lock up, she rolls her eyes and says “Oh, you’re turning into the bloke again, aren’t you? The guy that does the shows.” And she’s sort of right. The opposite happens when I come back. After you’ve had people telling you how marvelous you are, you don’t really feel like emptying the dishwasher.

Your songs paint these honest, self-reflective little stories from life, but you’ve said your songs aren’t autobiographical.

When I write, I think of myself more as a craftsman. Like a Tin Pan Alley guy. I’m always trying to make the song sound easily accessible — almost surprisingly accessible. I’ve always got a commercial eye out. And [as a listener] when a song is very autobiographical, I’m not very interested for some reason. I like stuff that appeals to everybody. [Only] Bob Dylan manages to write autobiographical songs that apply to everybody. They don’t sound like some dreary, meandering thought that no one cares about.

Seeing you live, your new songs are often a highlight of the show. I don’t know how many people 50 years into their career can write songs that click with big fans and with people just now discovering your work.

I’ve noticed far more younger people at the shows — a lot more women as well. It used to be mainly bald old men stroking their chins to see how much rock and roll there is in it. [The young people] like the old stuff well enough, but they couldn’t care less, really, about [its release date]. They just take each song on face value. One of the songs that goes over great is “Trombone,” and that’s a new song. I have this kind of jokey thing that I say to the crowd “We’re going to do a new song, but don’t worry, the new stuff sounds exactly like the old stuff.”

A highlight for me is “Blue on Blue.” What were you going through when you wrote that?

It’s quite a desperate song. I wrote it in Italy when we were on a holiday over there and it was extremely hot. So you stay indoors and close all the windows and it was all dark. Part of the power of it is that one bit leads to another very naturally as it unfolds. My songs aren’t necessarily autobiographical, but I can put myself into a character very easily. I can really imagine that I am that person or that creature. And so it was with this song. It’s got an odd lyric. It’s the classic “I love you so much that I hate you sort of thing” and “I can’t live without you, even though you are just vile.” I’ve written a few songs on that theme, and I think it’s fascinating. Because I’ve known a number of people who’ve lived like that.

For a British artist, your fanbase is distinctly American. How did that happen?

Well, when Will Birch wrote his biography of me, I discovered that my great-grandfather was actually American — which was a surprise to me, I must say. But it explains certain things. I’ve always had an understanding with American things, even from when I was a kid. Certainly the music I’ve enjoyed has always been American. Then my first marriage was to Carlene, and that’s when I met Johnny Cash and June. But really, I found an audience in America very early on with Rockpile. We did lots and lots of touring over here and the reason why I enjoy such a nice audience in the States now is in no small part due to the work I did with Rockpile.

Considering your background with Elvis Costello and the English punk scene, why have you never really incorporated any kind of political or social issues into your songwriting?

I’ve always thought there’s something incredibly irritating about pop singers going on about politics. Especially if they’re sanctimonious and sort of nannying about it. They might be right, they might be wrong, but my immediate thought is always “Why don’t you just shut up and get on with writing a decent tune? Keep all that stuff to yourself. You’re doing alright, mate, don’t be the voice of the huddled masses.” I like stuff that’s got heart and makes a point through a humorous approach. There are very few people who write overtly political songs who can manage to do that well. There’s something tedious and tiresome to me about the all the posturing that goes on in the music business. I just try and stay away from it and act like Elvis.

Not Costello.

No, not Costello. I keep on using the word “entertain,” because I do think of myself as an entertainer. I don’t have a point of view that I want to push at people other than “Be nice. Be nice to each other.” That’s about it, you know?

When did you notice that music was your “thing”?

Oh, I think I was pretty young when that happened. I had a little plastic banjo with this little gadget that clipped onto the neck with buttons you press and pads that held the strings down. It didn’t take me long to think that this gadget was a bit uncool and I might be better if I actually learned how to do the chord. So my mother showed me how to do them, and once I’d got into that, people seemed to be pretty impressed. I was quite keen on impressing people with my rendition of Lonnie Donegan songs. He was my first hero. I liked that feeling and I really didn’t want to do anything else. I didn’t do well at school. I didn’t pass any exams, but I knew all of Eddie Cochran’s and Chuck Berry’s songs. As soon as I got an opportunity — when my school friend Brinsley Schwarz phoned me up and said “Do you want to join our group? We’re going to chuck out our bass player,” I was off.

Do you have a favorite album and song of yours?

There’s something wrong with all of them for me, but I like The Convincer because that was the [first one where] I could hear something really coming into focus. I also like The Impossible Bird, although it didn’t sound right to me at the time. I sort of like it more now, actually. But I don’t really listen to my own records. I do when I first do them. I listen to them sort of obsessively, really, but then suddenly one day you wake up and you just don’t want to hear ’em anymore.

What was it like meeting Johnny Cash for the first time?

It was at his house in Nashville — a huge house on the lake. Carlene took me over there and he was in bed. He was lying in bed, reading the paper, propped up like an emperor.

Why was he in bed?

He just hadn’t gotten up, but he had just finished his breakfast and he was extremely friendly and nice. I think he had a silk dressing gown on, and his pajamas done up to the top button, I remember that as well. The house was full of antiques — those incredible antiques that they bought from Europe.

And he said?

“Hi Nick, I heard a lot about you.” But I can’t remember too much about the conversation. I was too busy sort of going [mimics a big gasp]. But there is a funny story about that house. Whenever Rockpile played in San Francisco, there was a Howard Johnson’s hotel in Mill Valley that we used to stay at. I told Cash about this. Mill Valley was nice and it was convenient for the city, so he started staying there.

Many years later, after Johnny Cash died, somebody from my record company called me and said “Nick, we got this sort of mad person who has contacted us. She says she’s got something for you. She’s got a document for you. We said ‘We’ll send it along,’ but she said she’s got to give it to you in person. We tried to get rid of her, but she won’t go away.”

I said, “Well, let me have a talk with her.” So I spoke to this woman and she told me this incredible story. She said that she had been a receptionist on the front desk at Howard Johnson’s, and Johnny Cash was staying there and he knew we were coming in a few weeks’ time. He wrote me a letter and he gave it to the woman on the front desk and said “Look, can you give this to Nick when he comes with Rockpile?” And for some reason or other, she never did. Either she forgot or maybe she decided to hang onto it. Anyway, she said “Look, I’ve got this letter. I’ve opened it. I’ve had dinner parties where I’ve shown it to people… I’m older now. And I feel so guilty about this. I thought the only thing I can do is to ‘fess up to you. I’ve had this letter all this time. And I’ve treasured it. I promise you I’ve treasured it, but I have kept it. And now it’s time for me to own up and I want to give it to you back.” I said, “Of course, I don’t mind at all.”

So she sent me this letter and it was very carefully opened. She hadn’t just ripped it up, she’d opened it with a letter opener and it was in a cellophane bag. So it was like new.

What did it say?

This letter was amazing. It was about 12 pages, and he’d obviously had a couple of drinks when he wrote it, because it was ranging around. He was talking about “I just heard this Pink Floyd track called ‘Comfortably Numb’ and I really think I could do a great version of this song.” So it had all this stuff in it. But one thing was quite amazing, right at the end.

I think the reason he’d written me this letter was because I’d written to him soon after I’d married Carlene saying “Look, John, everyone’s asking me about you and sometimes I say things which might sound a little rude in print. They sound funny when I say them, but they might sound a bit rude. And I’m just writing to say, look, I’m really sorry. I’m trying to handle this. Everyone’s asking me about you and I want to do the right thing, but at the same time, I don’t want to be a sap about it. So if you read something that seems a bit bad or ill-mannered, try and believe me. I think you’re the greatest sort of thing. It’s taken out of context.”

In the letter, he addresses this. And right at the end, he says “Don’t worry, I know exactly how that goes. Just go for it. We’re going to get on just fine and you are always welcome ’round at my house. And if you ever feel you’re not, I’ll burn the place down.”

And then five years after he wrote the letter, Barry Gibb bought that house and it burned down about a week later. [Laughs.]

So in between him writing the letter and you reading it. Let’s say there’s a knock on the door and it’s Johnny and June. What are the first 10 minutes like of that visit?

June was sweet. She was so natural and effervescent, so she’d just go for it. But John was sort of a shy man. It was very difficult for me because he was so incredibly charismatic when he was in the room, it was unbelievable. It’s almost like he had trouble with it himself — you know, dealing with his own charisma. But it wouldn’t take long before we relax and he generally asked me a very direct question. “Do you have many power cuts around here? Where’s the nearest garage? I was just going to take a walk, get some cigarettes,” or something like that. And then it’d be fine after that. He was a smashing guy. I still miss him.

Photography by Keeyahtay Lewis.