This story was originally published in the May 2008 issue of SPIN magazine.

This should be a remembrance.

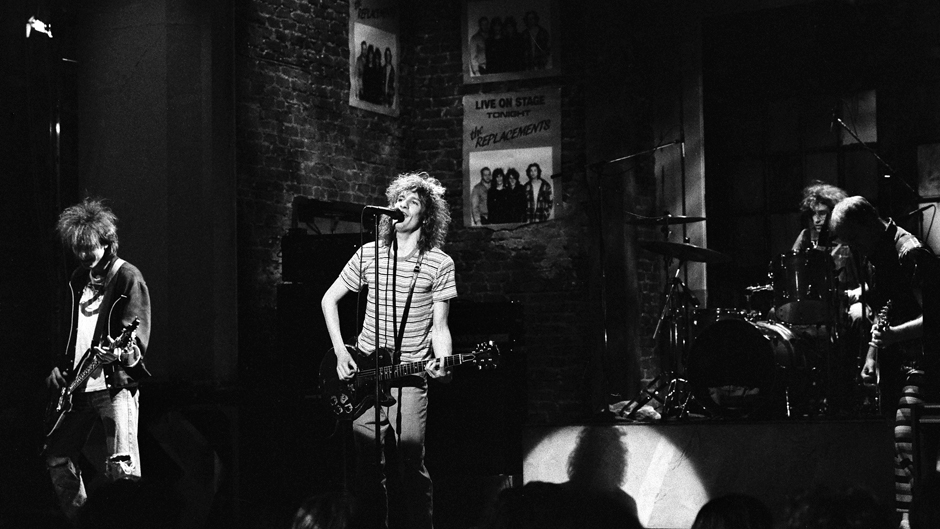

After all, the Replacements, that most beloved and confounding of alternative bands, broke up in 1991. The group’s larger-than-life guitarist, Bob Stinson, has been dead for 13 years. Drummer Chris Mars is no longer an active musician but a respected painter. Bassist Tommy Stinson, now of Guns N’ Roses, has been Axl Rose’s lieutenant for a decade. And singer Paul Westerberg, in between fitful stabs at a solo career, has largely repaired to the quiet of life as a family man.

Still, in 2008, something is stirring.

Also Read

Every Replacements Album, Ranked

The band’s influence — not so much a specific sound or a style, but an undeniable spirit — has never really abated. Successive generations of wildly disparate bands, from Nirvana to Wilco, Drive-By Truckers to the Hold Steady, have paid homage in their own ways. But this year, the Replacements themselves will be making a comeback with a concerted campaign that will see the group’s entire discography reissued. More than just improving the sound of the original records, the packages — expanded, bonus-laden affairs — make a case for the music, something that’s often taken a backseat to the band’s brilliant, besotted legend. The reissues offer a substantial marker for the group, but not a tombstone.

“Oh, the fucker still lives,” Westerberg says, cackling. “The monster that is the Replacements is still alive and ready to suck anybody down who wants to be a part of it.”

It’s an unusually warm mid-February day in suburban Minneapolis, as Paul Westerberg trudges through the back door of his house. “I’m breaking the cardinal rule,” he says, wiping his feet on a mat. “Never let a writer into your home.”

Westerberg leads the way into an airy, unassuming spread he shares with his wife, author Laurie Lindeen (former guitarist for ’90s alt poppers Zuzu’s Petals), and their nine-year-old son, Johnny. The decor — baby grand in the front room, guitars strewn about, rustic oil paintings on the walls — is much like the man himself: rock’n’roll elegant, yet resolutely Midwestern.

“Watch out for the ice skates,” he warns, entering a cluttered sunroom, where he plops himself into a rocking chair. At 48, Westerberg has taken up hockey. He spends a couple hours each day at an outdoor rink nearby, skating himself ragged. “It’s been a good diversion for me,” he says. “But it’s also a way to keep in shape, in case I have to play again. I don’t ever want to be caught not ready to go.”

By his own admission, Westerberg leads a fairly hermetic existence: He doesn’t drive, doesn’t socialize, and splits his time between his basement studio — where he’s made all of his recent records — and raising his son. Even amid the domestic trappings, there is the odd reminder of his reputation.

“The other day,” he says, “I was helping coach my son’s basketball team. I had this SpongeBob hat on, and this kid came up to me and said, ‘Why are you wearing that? You’re a rock star.’ And I was like, ‘I’m the coach, dude. Go do a lap.’ If I’m here, I’m not Steven fucking Tyler, y’know?”

Between 2002 and 2005, Westerberg was hard to miss, releasing five solo albums, a best-of-compilation, and a DVD, as well as doing a couple tours, including his first full-band jaunt in nearly a decade. Since then, he’s eased back, composing songs for the soundtrack to the animated film Open Season and recovering from a freak 2006 household mishap that severely damaged ligaments in his left hand. Although he’s given recordings of 60 new songs to his manager, Westerberg says he has no burning desire to release another album, considering the record business’ current climate and his distaste for promotion.

Mostly, for the last few months, Westerberg has been fielding, or avoiding, calls about the Replacements. Rhino Records has just released remastered, expanded editions of the band’s four albums for Minneapolis indie label Twin/Tone. (Reissues of the group’s four Sire titles will follow in the fall.) The process has forced Westerberg and Tommy Stinson — the two principals in the Replacements’ affairs — to face their pasts together. In turn, that’s spurred talk of recording new songs and, perhaps more tantalizingly, reuniting the band onstage.

“I’m still in the Replacements,” Westerberg tells me at one point. “I never pulled the plug on the group. If there is a Replacements, I’m still in the band. No one can kick me out.”

The popular notion of the Replacements’ birth has always had a whiff of the Immaculate Conception about it. As the story goes, Paul Westerberg — high school dropout, aspiring musician, part-time janitor — was on his way home from work when he heard the sound of Chris Mars and the Stinson brothers jamming in a South Minneapolis basement and — voila — the Replacements were born. While elements of that story are true, and you could argue that the Replacements were simply meant to be, their leader’s musical career was no accident.

“I’m a ‘no photo’ in the yearbook for two years,” says Westerberg, peering out from behind thick eye glasses and running a hand through his tousled hair, “because I knew someday people would come back and look for it. I’d known since I was about age nine that I was gonna do it. People would ask, ‘What are you gonna do, man? You gonna be a rock’n’roller?’ And I’d keep my mouth shut, but I always knew.”

The third youngest of four kids, Westerberg grew up around music. His uncle played in local lounge bands, and he fondly recalls spinning his big sister’s British Invasion and Motown singles, and hanging around with his older brother’s blues- and bluegrass-obsessed buddies. At 13, he bought an old acoustic guitar off his sister and fumbled away in his bedroom for a couple years, before getting his hands on his first electric, which prompted a neighbor to leave a stack of instructional books on his front porch.

For much of the mid- to late 70s, Westerberg kicked around town playing guitar in dozens of short-lived bands with names like Oat, Velvet Hammer, and Cunning Stunts. He played Southern rock with hippie stoners, jammed with a crew of Sabbath-obsessed metalheads, covered Beatles tunes with note-perfect precision. “I spent a lot of time just learning to be a hotshot guitar player, until I realized that was nowhere,” he says.

The realization hit him hard one day at a friend’s house (“the one with the good weed and even better records”) when Westerberg heard the Sex Pistols for the first time. “The song was barely over before I’d gone home and cut my hair off and smashed all my records,” says Westerberg. “Hearing [John] Lydon’s voice made me think, ‘Forget all these solos I’ve been trying to play — I’m gonna sing. I’m gonna lead a fucking band.'”

The chance came when a friend dragged him over to the Stinson house one Friday night in late ’79 to see a fledgling group called Dogbreath. Westerberg walked in and immediately recognized drummer Chris Mars from the old neighborhood — they’d grown up a block apart as kids. He’d seen Bob Stinson, too, traveling downtown on the Bryant Avenue bus. But what really caught Westerberg’s attention was the bassist in the corner, Bob’s 13-year-old brother Tommy. “This little kid, whose amp was taller than he was,” says Westerberg. “He just looked like a star…and played like a motherfucker.”

Squinting into the bright California sun from under a black fisherman’s cap, Tommy Stinson extends a hand. ‘”Sup, dude?” he offers in a bubbly Minnesota accent, looking considerably younger than his 41 years. “How ya doin’?” It’s early February, and Stinson is standing in the courtyard of a stylishly retro home in Los Angeles’ Silver Lake district. It’s the place he shares with his sometime bandmate, drummer Gersh. Stinson moved in a couple years ago and took up residence in the downstairs recording studio with the idea of working on film and TV scores when he wasn’t at his day job playing bass with Guns N Roses. For the past decade, Stinson has been riding shotgun with Axl Rose. “That sounded more punk rock than anything I’d heard in a while,” says Stinson of his decision to join. “It’s creative, and it also pays me. I’m lucky in that regard after all these years.”

Taking a seat behind his computer, Stinson fiddles with some tracks he’s been working on for his daughter from his first marriage, Ruby, a high school senior and aspiring singer. Meanwhile, the screen shows a picture of Tallulah, the month-old baby he has with his girlfriend, Philadelphia musician Emily Roberts. In a few weeks, he’ll leave Gersh’s for good and get a place with his young family just down the road. “I really want to have a home,” says Stinson wistfully. “It’s kind of weird to be transient your whole fucking life.”

Born in San Diego, Stinson shuttled around California, Florida, and finally Minnesota, moving a dozen times before he’d finished grade school. Raised by his single mom, Anita, older half brother Bob, and a pair of sisters, he had a bleak and unsettled childhood.

“Bob’s dad wasn’t around…and my dad was a rotten fucker,” recalls Tommy. “We left my dad in the middle of the night and moved to Minneapolis on a Greyhound bus. I remember suddenly being there with snow all around, living at my grandmother’s house.”

Growing up, Bob was in and out of group homes, reform schools, and rehab. With no male role model around, Tommy began to get into trouble himself. “I’d already been to jail three times by the time I was 11 for stealing shit — obviously, I wasn’t very good at it,” he says. “They were about to send me away to some juvenile home for a long time. And that’s right when my brother came back home and saw me fucking around with the bass and showed me how to play.”

For Tommy, music was a reprieve from a life that seemed destined for either prison or the morgue: “My prospects from where I came from weren’t great. But that was the thing about the Replacements: We were all nowhere — we came from nowhere, we were going nowhere. And the band gave us something.”

That hunger was exactly what drew Westerberg to the Stinson brothers and Mars during their first meeting. “I’d already fucked around with guys who really didn’t want to go for it,” says Westerberg. “All these other dudes were in it for the chicks or in it for the weekend, or were eventually gonna go off to college. And it took me a long time to find guys who had no other fucking options. I needed desperation. ‘Cause that’s where I was coming from.”

Westerberg schemed to get rid of one vocalist, then another, before claiming his spot as frontman. The group had been playing a handful of originals that Mars had written — intricate tunes with lots of stops and starts. Westerberg balked at learning the material, but floundered writing his own songs. “Finally, I saw something in a guitar magazine,” he says. “Shit, maybe a Ritchie Blackmore quote: ‘You’re either a genius or a clever thief.’ I thought, ‘Okay, I’m no genius,’ so I went and ripped off a bunch of Johnny Thunders songs and rewrote them. And that was it. We never looked back.”

Within months after their fateful meeting, the band — first named the Impediments — recorded a handful of Westerberg originals and passed the demo on to Peter Jesperson. A Minneapolis music-scene mover, Jesperson managed the hip Oar Folkjokeopus record store, DJ’d at the Longhorn club, and was partnered with engineer Paul Stark at local label Twin/Tone. After popping in the tape one day at the shop, Jesperson flipped, calling friends to come down and confirm that he’d not lost his mind and had actually just heard the greatest rock band ever. Sounding like a tussle between Chuck Berry and the Sex Pistols, the demo tracks — a quartet of songs included on the reissue of the band’s debut, Sorry Ma, Forgot to Take Out the Trash — were a revelation. A combination of dumb luck and benign alchemy had, almost overnight, turned the Replacements into a fully formed outfit that could, and would, change lives.

“Certainly changed mine,” says Jesperson, now a senior vice president at Los Angeles-based indie label New West. “It wasn’t like, ‘Oh, this could develop,’ or, ‘If they work on this and this, they’re gonna be a great band.’ No, it was like: ‘Oh my God, everything is in place already.'” Jesperson’s first taste of the future came during an ill-fated concert at the Bataclan, an old church that had been converted into a kind of halfway house for alcoholics and drug addicts. “I dunno how we got the gig,” says Westerberg. “All I know is that Bob and I were in the basement doing blow, and by the time we came upstairs, Chris had already been ejected from the premises — literally tossed out on his ass and down the stairs as Pete Jesperson showed up.”

This was a sign of mayhem to come for Jesperson, who served as the band’s label boss, manager, cheerleader, and babysitter for the next six years. (He also became Tommy’s legal guardian on the road.) Though he sometimes cringed at their antics, he never tired of the music’s visceral thrill. “They didn’t do any song the same way twice, and they didn’t make set lists or follow any sort of rules, so every night they went out there trying to figure out another way to get themselves off,” says Jesperson. “And the feeling was, if they got themselves off, then the audience would get off, and then all of a sudden you’d have a bunch of people in a room getting off together.”

With Jesperson and Twin/Tone offering a support system, the band turned out four records in just over three years. The first two, Sorry Ma… and Stink, were snotty, amphetamine-fueled affairs that saw them fall in with a clutch of punk and hardcore bands, including fellow Minneapolitans Hüsker Dü.

Although the Replacements were growing exponentially as musicians — and Westerberg’s songwriting was revealing a more personal, somber side — they found themselves mired in a dogmatic scene. The ‘Mats —short for Placemats, as they’d been nicknamed — began baiting audiences, offering loping country covers to frenzied skinheads and breaking out tender ballads in front of seething hardcore mobs.

“I was a fast learner,” says Westerberg. “I figured out that danger was what people sought. And there was a certain danger that we were capable of that wasn’t your usual thing about destruction, or ‘We’re going to hurt you.’ It was: What if we get up there and played a song by Hank fuckin’ Williams? It’s like, that’s going to piss them off. That’s why, early on, I acknowledged the softer side of the music, too, ’cause I knew that would rub a lot of people the wrong way.”

They began to win acclaim and a national following after taking their music in manifold directions on 1983’s Hootenanny and 1984’s Let It Be. It was also around then that alcohol — at first used to steel their nerves — became part of the band’s presentation. Featuring heroic pre-show drinking sessions, the tours became traveling Irish wakes. Any concert might be both the best and worst show they’d ever played — an encomium that, one suspects, the band perversely savored.

On the strength of Let It Be and the attendant critical hoopla, they signed to Sire in 1984. A year later they released Tim, another minor masterpiece. But turmoil hit the group in 1986: They let Jesperson go as manager, signed with a larger firm, and fired Bob Stinson, who’d become an increasingly erratic presence onstage and off. “My brother was becoming a hindrance to [Paul’s] songwriting growth and to what we were doing,” offers Tommy wanly. “He was just messed up. We were all messed up, but we were messed up less than him and could forge on.”

The decision was not an easy one, but it ultimately served to bond Tommy and Westerberg. “We clung to each other, because we realized that the first run of the band was dying,” says Westerberg. “It was like, ‘Do you want this ship to keep going?’ In essence, [Tommy] stepped up to save the band.”

After the tumult of’86, the vibrant Pleased to Meet Me — recorded by the band as a trio — came the following year, as did Bob Stinson’s replacement, Minneapolis guitar veteran Bob “Slim” Dunlap. The band then recorded the glossy pop of 1989’s Don’t Tell a Soul, alienating many longtime fans. Disinterested in the group’s new direction and hurt by Westerberg’s public criticism of his playing, Chris Mars left before the release of 1990’s bleary-eyed swan song, All Shook Down. Initially intended as a solo album for the newly sober Westerberg, it marked the slow, inexorable grind of the group’s final days, which ended with a muted farewell performance at Chicago’s Grant Park on July 4,1991.

Westerberg says now that the chase for commercial success that dominated the band’s latter years was ultimately what doomed them. “The goal became simplistic and unrealistic, which was to have a hit,” he says. “And that’s where we died. We weren’t made of the stuff that makes popular music.” When I ask Westerberg what might have been if they’d had that one radio smash that made them stars, even briefly, he laughs. “Well, you wouldn’t be here today,” he says. “The fact that we came up short is the thing that’s kept us interesting. We’ve retained this mystique. And I don’t know how, ’cause goddamn it, we tried. We tried to have hit records there at the end. And someone was looking out for us that we didn’t.”

One frequent comparison that crops up is between R.E.M. and the Replacements. Contemporaries, collaborators (Peter Buck played guitar on Let It Be‘s “I Will Dare”), and tour mates, at one point both indie bands seemed poised for mainstream success. Now, R.E.M are multimillionaires, while the ‘Mats are consigned to the margins of music history.

“Well, we sorta lived with them for a year, and we saw what they did to get to where they wanted to go,” says Westerberg. “When it came our turn, we visited the record distributors and met with the radio programmers and did all of that stuff. But, in the end, we just felt like we had to piss on the guy’s shoe. Look, we got to the party. But instead of embracing it, we huddled together in the corner and said, ‘Fuck it — let’s get out of here.'”

Given the Cards we were dealt,” observed Tommy Stinson of the Replacements in the late ’90s, “our legacy is all we have.”

But the knotty personal and band politics within the ‘Mats have made caring for that legacy a tricky task. There have been some token efforts: a 1997 best-of/rarities set All for Nothing/Nothing for All documented their Sire years; Don’t You Know Who I Think I Was?, a 2006 career-spanning comp, boasted a pair of new tracks featuring Westerberg, Stinson, and Mars. But while various proposals for a comprehensive box set and expanded album reissues had been mooted since the early ’90s, nothing ever came of them.

This was partly due to the fact that the band’s Twin/Tone masters changed hands numerous times. Further complicating matters was Bob Stinson’s 1995 death. Following years of drug and alcohol abuse, his body simply wore out, and his passing only further clouded the band’s desire to revisit its past.

Finally, after several frustrating false starts, a proper Replacements reissue campaign got the green light last summer with Jesperson — who remained the band’s de facto archivist and most ardent champion, despite his dismissal — overseeing the project for Warner’s Rhino division. In August, Jesperson transferred his entire archive of Replacements DATs to disc, some 57 CDs’ worth of material from the band’s first six years — every studio session and home demo — compiling a master list of bonus tracks for the band’s approval.

Tommy took a more active role than the others, helping mix some of the unfinished outtakes at his home studio. “I sat and stared at those CDs before I ever played them. I really didn’t know if I could go back there,” he says. “When I finally threw them on, it was cool. I heard my brother and me laughing on one of the tracks, and it was pretty emotional. Ten years ago, five years ago, even, I couldn’t have listened to this stuff.”

Much of what makes this first batch of reissues so interesting is hearing Bob Stinson’s guitar work, and the charmed collision between his primordial playing and Westerberg’s rapidly developing songwriting. “Bob and Paul didn’t fit together; they were like cramming square pegs in round holes the whole time,” says Stinson. “But it still worked somehow, and there were times where it really worked.”

In the past, Westerberg had been dismissive of Bob’s playing, but he says relistening to the early records gave him a new perspective. “Most lead guitar players are frail and full of themselves and spend a lot of time noodling,” says Westerberg. “But Bob was a guy who picked up guitar in reform school, learned how to play a few Johnny Winter songs, and then just beat the shit out of the thing for all the frustrations in his life. He could fucking wail, yet he didn’t know where he was going. But he had the confidence not to say, ‘Oh, shucks, I fucked up there.’ If he fucked up, he would fuck up with majesty.

“I think of him every single day,” Westerberg continues, shaking his head. “Mainly ’cause I got a ringing in my left ear from having him blasting away next to me all those years.”

To Jesperson, the reissues represent an opportunity to put the emphasis back on an oddly overlooked aspect of the Replacement’s legacy: the music.

These days, even younger bands who sound like the Replacements know more about the band’s legend than their songs. “I’d never actually heard them,” says Parker Gispert, the 25-year-old frontman for the fast-rising Athens act the Whigs. “I’d read about their antics, but then we started getting compared to them, so I got the records and just nerded out. If there are similarities, I’d say it’s more about spirit — they wrote pop songs but played them hard and fast and maybe that’s what we do, but I don’t sound anything like Westerberg. His voice is shit tons better than mine.” Jesperson hopes others follow Gispert’s lead.

“There were a lot of times where I honestly felt like it was impossible that there was a better rock’n’roll band on the planet,” says Jesperson. “I’d just be watching them and say, ‘Here it is — this is Elvis Presley, this is the Rolling Stones, the Sex Pistols, this is all of that. They’re doing it.’ I think some people who might be a little bit on the fence about the Replacements’ place in rock history are going to change their minds.”

All this talk about the Replacements’ past has suddenly heated speculation about the band’s future.

Late last year, after more than a decade, Westerberg and Tommy began spending time together in Minneapolis, even trading a few song ideas. Out of those visits came discussions of a ‘Mats reunion.

One tentative plan was for a Replacements lineup — possibly rounded out by session drummer Josh Freese and an undetermined lead guitarist — to do a handful of shows on the lucrative summer festival circuit, as well as some bicoastal theater dates. A couple of months ago the idea had gained serious momentum; now the prospect seems uncertain.

The willingness to consider a reunion at all is something of an about-face for Tommy, who as late as ’05 was ruling out the possibility of it ever happening.

“Working on the reissues, I got really wrapped up in that shit, and I had to rethink my previous stance on it,” says Tommy, who played three songs with Westerberg and Freese at the 2006 premiere of Open Season. “We don’t need to be the Replacements anymore; we’ve done it. But we’ve got unfinished business, if we want. And if Paul and I can hang out and play together and enjoy each other’s company, why not do it? At least until I hate him again.”

Tommy’s wariness is understandable, since Westerberg has occasionally stung him privately and with comments in the press. “Paul tends to make jabs without meaning to make jabs or hurt anyone’s feelings or be an asshole, but it comes off like that,” says Stinson. “We all have to be accountable for the shit we say and how it affects people. If you want to go down that road, you lose friends. And why go through that?”

Though the interpersonal rift has largely been resolved, the bigger stumbling block for Westerberg, at least, seems to be the ghost that still haunts both the Replacements and his relationship with Tommy.

“The answer to the million-dollar question is yes, when Bob [Stinson] died, something died in me and Tommy, and we’ve never been the same since,” says Westerberg. “And it’s always been awkward, and it’s always been unsaid and unsayable and strange and weird between us.”

Westerberg painfully recalls sitting in the back at Bob’s memorial service, apart from the rest of the band, his heart sinking as the PA blared a requiem of songs from Sorry Ma… and Stink. “So, now, to release the first four records and for me and Tommy to get back together to celebrate that is…difficult. It’s difficult to do it without that goddamn guitar player, or at least without Chris.”

Mars — enjoying a rewarding career as a surrealist painter — insists he has no interest in playing with the band again. “I sincerely wish the best for the two of them,” he says. “I would want nothing less than to see Paul and Tom to carry on with the Replacements happily and successfully without me. I really mean that.”

Despite Westerberg’s misgivings, part of him seems intrigued with the idea of bringing back the Replacements, if not to compete with the bands they’ve influenced, then perhaps to see if he can measure up to his younger, more inchoate self. “When I listen to those first few records, I hear myself, and that guy is closer to being born than I am to his age right now,” says Westerberg. “And I think, ‘Could I go out and do that again?'”

At this point, finding a way to play without tarnishing the band’s weighty legacy seems to be a nagging worry. “Would we fuck up the legend by doing it?” asks Stinson. “Why get bogged down in that? We could just go out and have fun, play the songs and not try to live up to the legend.”

“I told Tommy, ‘Let’s have auditions,'” says Westerberg. ” ‘Let’s you and me go onstage and play 25 songs, and we’ll have a different guitarist and drummer come up for each song, and that’ll be the show.’ That would be the only thing the Replacements could do to keep up the honor of the name, rather than go and just cash it in.”

Tommy, who’s biding his time recording new solo material while he waits for Guns N’ Roses to ramp up again, says that as far as the Replacements reunion goes, the ball is in Westerberg’s court. And given Westerberg’s decidedly mercurial nature, it’s hard to tell what he’ll decide. “I’ve run out of confidantes — and confidence, as well,” Westerberg says, chuckling. “There’s no one I can really turn to and ask, ‘What do you think I should do here?’ I mean, if Tommy pulled up in my driveway in a flatbed truck with instruments and a band and the songs ready, on the right day, I might hop on and go. If it was this afternoon, I wouldn’t. I’ve gone each and every way with it, and I really don’t know anymore.”

And that’s just it: Westerberg doesn’t know what his future holds any more than he knew what was coming when he stepped into the Stinsons’ basement nearly 30 years ago.

Except that maybe, just maybe, the Replacements’ story isn’t over yet.