Release Date: April 01, 2016

Label: Partisan

Patriotism may be the last refuge of scoundrels, but musical censorship runs close behind. Be it plantation owners confiscating the drums of African-American slaves, or Nazi propaganda snuffing out Yankee jazz degeneracy, musical expression remains a favorite soft target for dictators and reactionaries alike. And while failed attempts by the Taliban to ban all musical instruments from Afghan society have grabbed headlines, a more recent act of overt musical aggression came via the government of Niger’s desperate decree banning guitars among the nomadic Tuareg people of the Sahara, ostensibly to tamp down an ongoing insurgency/rebellion within Mali and Niger. The guitar ban proved a dismal failure — if anything, the instrument has assumed greater centrality within contemporary Tuareg culture.

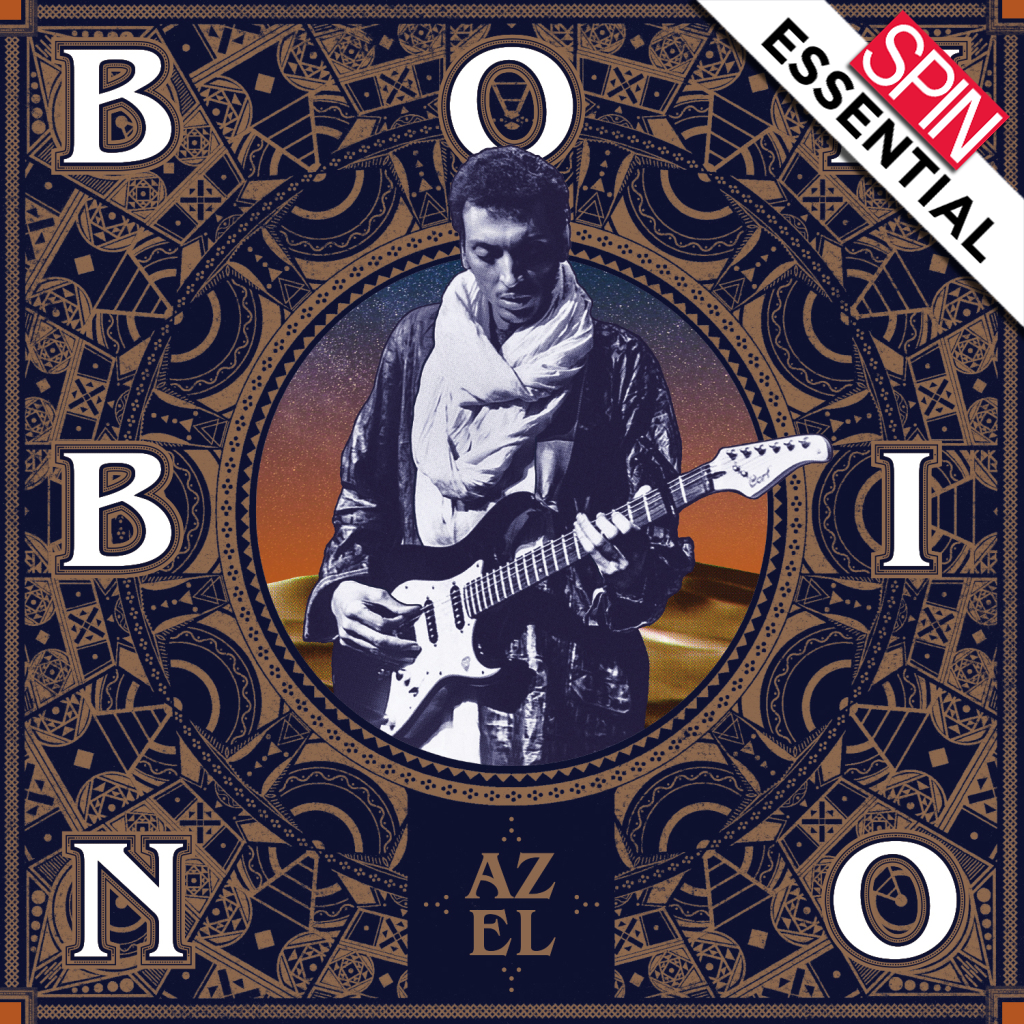

Unsurprisingly, American and Eurozone fans have been receptive to the circular licks and percussive syncopation of what’s lazily referred to as “desert blues” (the practitioners prefer “tishoumaren”), as guitar-dominated Tuareg ensembles Tamikrest and Terakaft have followed the lead of grandaddy outfit Tinariwen. Expanding their audience far beyond the Sahel, these bands have turned a unique mélange of Chaabi protest, Algerian Raï, Western rock, and ancient Berber folk tunes into music for small ensembles dominated by intricate riff-work, a technique first perfected by Tinariwen guitarist Ibrahim Ag Alhabib in the late 1970s. And Ag Alhabib has no finer pupil than Omara Moctar, a.k.a. Bombino, perhaps the region’s most accomplished virtuoso and the biggest Dire Straits fan in all the Sahara.

A six-string prodigy along the lines of fellow polymath Taj Mahal, Bombino supplemented lessons learned at the feet of mentor (and fellow renowned guitarist in his own right) Haja Bebe with close studies of old Jimi Hendrix and Carlos Santana footage. Some of those rock moves have made their way into his arsenal, but Bombino isn’t a shredder in the clichéd guitar-hero mode — his fluid technique and improvisational gifts are marked by restraint, epitomized by the convent-pure tones of “I Greet My Country,” a mellifluous track from his third album, 2011’s beauteous Agadez, that brings to mind the sweet electric shivers of Sonny Sharrock’s Guitar-opening “Blind Willie.” Bombino’s altogether more raucous follow-up, 2013’s Nomad, paired him with Black Keys guitarist Dan Auerbach as producer, upping the blues-rock ante courtesy of a German drummer and a mix dusted with such Western exotica as vibes and pedal steel — hardly traditional, and no less enjoyable for that.

Those who fret over the dangers of cross-pollination won’t necessarily be soothed by Bombino’s fifth album, Azel, which should delight the rest of us non-purists. Producer and Dirty Projector Dave Longstreth leaves extraneous instrumentation mostly to the side while favoring a particularly bright mix highlighting Bombino’s double-tracked guitar and a punchy drum kit. But the addition of female vocalist Mama “Mahassa” Walet Amoumine and periodic excursions into skanky Caribbean rhythms (wryly dubbed “Tuareggae” by Bombino) stamp Azel as yet another remarkable transition for the guitarist. Split-channel conversations with himself on “Iwaranagh” buoy one of the guitarist’s most melodically generous guitar lines, while the six-minute, crawling king-snake riff-monster “Iyat Ninhay / Jaguar” applies Led Zep bombast before indulging in a mid-point dub breakdown. Tuareggae, indeed.

Four all-acoustic reveries offer a change of pace. “Inar” and “Igmayagh Dum” match their Tamasheq lyrics of love with rhythmically lithe fretwork, the former suggesting a curious similitude with certain strains of British folk revivalism — the gentle simmer of Nick Drake’s conga-aided “Three Hours,” the circular pull-offs on Martin Carthy’s “Famous Flower of Serving Men.” Despite Bombino’s outspoken love for dad-rock favorite Mark Knopfler, there’s no sense of direct English folk homage on these tapestries, all of which owe much more to a regional acoustic affinity for so-called “dry guitar” (encompassing Kenyan folk, Sahel drone, and more). But closing tracks “Ashuhada” and “Naqqim Dagh Timshar” remind us that the delights of power chords and Brothers in Arms shouldn’t overshadow Saharan reality. “Ashuhada” is a rippling tribute to the dead from the 1990 to 1995 Tuareg Rebellion, while “Naqqim Dagh Timshar” translates as “We Are Left in This Abandoned Place” — a bleak tally of the damage done in Niger.

No doubt Western attention to the Tuareg cause has improved the lives of some of its musicians. Yet in spite of unflagging musical elation, the long Tuareg struggle for regional autonomy looms over Bombino’s loveliest compositions. After all, the young Omara Moctar fled to Algeria during said rebellion, only to once again pack up for Burkina Faso in 2007 after the Nigerien military executed two of his fellow musicians. That’s two forced exiles in 15 years for somebody well under the age of 40, so figure Bombino knows the weary blues with an intimacy denied to either you or me. And recall that, despite the soothing nature of the NPR-approved Tinariwen, many of the band’s members were originally rebel fighters, including guitarist Ag Alhabib, who received free military training at the behest of Libyan leader Muammar Gaddafi (who had hopes to bolster a Saharan regiment to better advance against Mali and Chad). Ag Alhabib also witnessed, as a 4-year-old boy, the execution of his father.

The blues are universal; the blues are also incredibly specific. As the Western pendulum of intolerance swings back toward the undifferentiated immigrant and the unnamed refugee, it’s to Bombino’s great credit as an artist, human being, and former asylum seeker that his acts of remembering a carry such a beautiful sense of plugged-in joy.