The ambient techno Wolfgang Voigt makes as Gas does not traditionally offer much in the way of linear progression. His tracks regularly extend to 10 minutes and beyond without major changes, offering environments to inhabit and explore rather than journeys to take. Voigt famously describes his best-known alias as an attempt to “bring the German forest to the disco,” or vice versa. Each track is a clearing or a mountain vista, with drums and shimmering strings standing in for flora and fauna. You’re not walking through the woods, but waiting and listening, absorbing the stillness and splendor of each scene before moving on to the next. When a new synth pad or drum part arrives, these changes catch your attention for a moment and then fade back into the landscape, like the rustle of bushes disturbing an otherwise placid scene after an animal has escaped from a predator.

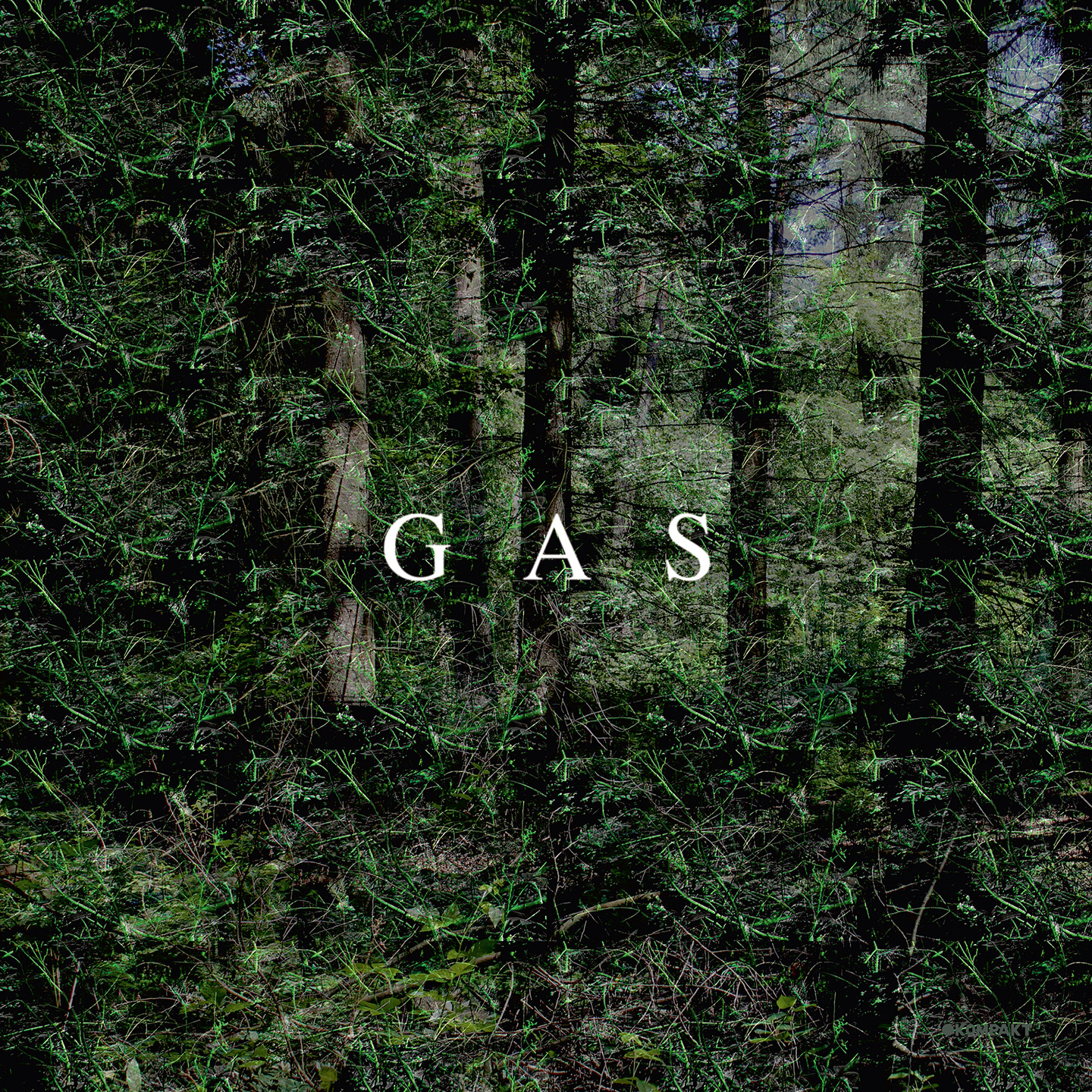

Like Voigt’s music, the Gas catalog is also built on small shifts that reward close attention. The release of the nearly career-spanning multi-LP set Box in 2016 reinforced the idea that each album can be considered as both an individual statement and a component of a larger work, just as a single track is a component of an album. (Box also reinforced Voigt’s well-deserved status as an electronic music luminary: Gas is one of countless musical endeavors he’s taken since emerging in the early ‘90s, including the co-founding of the seminal Cologne-based techno label Kompakt.) Each Gas record has its own character—1999’s Konigsforst is a bit brighter than ‘97’s ominous Zauberberg, 2000’s Pop leans hardest on the “ambient” side of the ambient techno equation—but they are like monoliths at Stonehenge, imposing on their own while belonging to a single larger aesthetic project. Visually, each album besides the first is distinguishable mostly by the color filter applied to the forest photo on its sleeve, all of which are taken by Voigt himself.

Rausch, the sixth Gas album, has a cover in deep pine-needle green. But after last year’s Narkopop, which found Voigt bringing the Gas project out of a 16-year slumber and masterfully reasserting its strengths, the latest release also marks a much more significant departure: the first that consists of a single piece of music: a composition that moves continually rhythm to atmosphere and back over the course of an hour, now and then receding to a thin vapor but never falling silent entirely. Like previous Gas albums, in digital versions Rausch is divided into numbered but untitled tracks. This time, however, those divisions are only there “due to format restrictions,” according to promotional materials. As a result, Rausch feels deliberately narrative in a way that previous Gas albums don’t, with each new zone arising from the last instead of presented independently.

This effect partly works in Rausch’s favor, offering a path through music that might otherwise seem impenetrable. But it also risks a monotony that Voigt has rarely if ever succumbed to in the past. He has always favored simple kick-heavy beats, but on Rausch, he uses a 110 beats-per-minute loop without deviation as percussion for the entire album. Rausch also contains several leitmotifs, the most notable of which is a tapped ride cymbal that first appears about a minute and a half into the album and does not leave for the next half hour or so. Through sections of euphoric elevation and arhythmic grind, the cymbal is always there: mantra and nagging schoolyard taunt.

Finding and discussing notable moments of Rausch could be a misguided impulse, a bit like attempting to pinpoint the most beautiful edges and corners of Richard Serra’s massive minimalist sculptures of weathered steel. Still, the album is at its most striking when Voigt breaks from his relentless intensity, as in “Rausch 3,” when the harmonies clear like exhausted storm clouds for the sun, and “Rausch 5,” when an unexpected acoustic guitar suggests a placid return to earth after a long period of turbulence. At other times, just as a great and terrible monument by Serra might end up as a visual distraction for tourists in an airport terminal, Rausch settles naturally as background music.

Rausch’s ambitious structure is an incomplete but laudable step forward. If Narkopop was a belated capstone on the first era of Gas, Rausch might be the first real statement of a coming second phase. And its status as second-tier Voigt doesn’t necessarily portend dire things to come. In 1996, Gas’s self-titled debut album was a promising but half-formed work, which Voigt has since symbolically disowned, conspicuously omitting it from the Box set. Just as that record gave way to the classic Zauberberg, so might Rausch be a trail marker for further splendors.