Janelle Monáe occupies rarified air. She is an instantly recognizable face—magazine covers, Super Bowl commercials—but has no hit singles; a canonized artist without a classic album. She exists in a space shared by artists like Lady Gaga and Bruno Mars as old school capital-p Performers who restore your parents’ faith in modern music, but without any of the ubiquity. Frankly, it sounds great.

Existing in the outer orbit of superstardom has allowed Monáe ample room to chase her muse. The result has been records that could have been made by nobody else: Afrofuturistic epics about an android who falls in love with a human, presented nonlinearly and with the help of collaborators ranging from Of Montreal and Saul Williams to Prince and Erykah Badu. But that doesn’t mean Monáe ever quite found herself. As unique as those projects were, the narrative could be inscrutable to the uninvested; and for as ambitious as she was as a storyteller, her music is generally the opposite: studious homages to the greats of soul and funk.

She is now aiming to change that. “I knew I needed to make this album, and I have put it off because the subject is Janelle Monáe,” she told the New York Times magazine. It’s not that her previous albums had none of her in them—they were centered around a character, Cindi Mayweather, whose love was denied by the government, encouraging the listener to draw a connection to Monáe, who recently came out as pansexual. But the pomp of her career—the multi-suite albums, the tuxedos, the Performing—presented her as someone incubated in a lab to entertain. Whether she lived a life away from the character was if not unclear, then at least irrelevant.

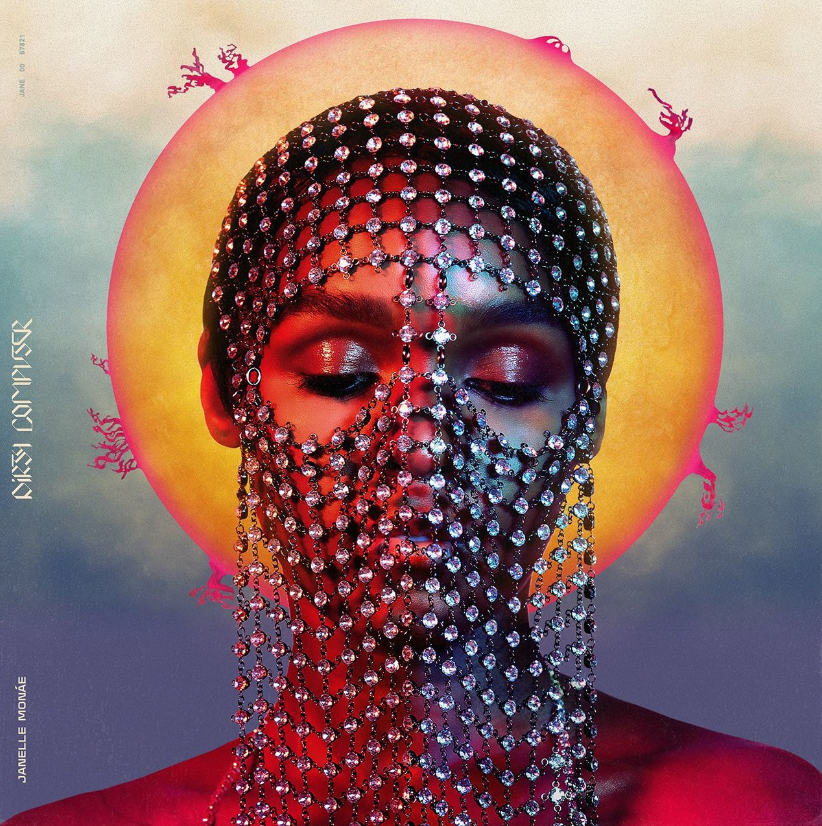

This is remedied overtly on Dirty Computer, her newest album. “A-Town, we made it out there / Straight out of Kansas City, yeah we made it out there,” she says, cleverly summarizing her personal come-up. “Mama was a G, she was cleaning hotels / Papa was a driver, I was working retail.” These lines are rapped on the song “Django Jane,” which helped introduce the album along with fellow lead single “Make Me Feel.” As a single, “Django Jane” was odd and awkward, offering up something—a Janelle Monáe rap song—that nobody really asked for. But within the context of the album it works as a moment of true triumph. It bleeds out of “Screwed,” a song about how sex can be both an escape and a protest during the apocalypse, and presented this way “Django Jane” feels less like a frivolity and more like a lynchpin of the album, with the blending of the personal and political heightening the impact of both.

If there’s any success unique to Dirty Computer, it’s Monáe merging her world and ours in a way that feels natural, even if it’s not always exactly coherent. “Everything is sex / Except sex, which is power / You know power / Is just sex / Now ask yourself who is screwing you,” she raps on “Screwed,” a fun little tongue twister that actually reveals truths when you begin to unravel it. Less provoking is that song’s outro, another rap verse that hinges on lines like, “Fake news, fake boobs, fake food, what’s real? / Still in the Matrix eating on the blue pills”—spaced-out mumbo jumbo that is more the province of people whose lives are disconnected from any tangible problems. Elsewhere, her sloganeering is blunt. The song “I Got the Juice” contains a refrain that goes “If you try and grab my pussy cat, this pussy grab you back,” and though it lacks a certain nuance, it nonetheless feels like an era-appropriate moment of catharsis.

The album is best in its meatiest section, a run of songs in the middle of the tracklist that remind us that Monáe and her team—including the writers and producers Nate Wonder and Chuck Lightning—have the songwriting chops to justify their reverence. This extends even to “Make Me Feel,” the single produced by pop machine cogs Mattman & Robin and co-written by radio maestros Julia Michaels and Justin Tranter. As a standalone it’s far too reminiscent of Prince (Monáe seemed to mount a defense against this criticism by inferring that Prince was actually involved in its creation), but sounds much better when entered into a continuum of her own work, sandwiched by the pleasingly elastic “Pynk” and “I Got the Juice.”

Things do get ponderous at the end. “Don’t Judge Me”—which shares a soft shuffle and airiness with “Pink Cashmere”—is a naked admission of self-doubt, but drags at six minutes. “Americans,” in which Monáe sings from both the perspective of a chauvinist and a revolutionary, is a muddled and ineffective attempt at a subversive anthem. That it just makes you want to listen to “Let’s Go Crazy” doesn’t really help either.

Dirty Computer is a different Monáe album—explicitly personal and political—but it’s also not. Her ability to transcend her influences has always been song-to-song, and that’s true here, too. But it also feels like she is inching closer to a breakthrough: an album that fully lives up to her reputation and ambition.