Playing sad is easy. Sadness in music can often be as much of an aesthetic choice as the display of some sort of real vulnerability. You can listen to a number of rap or R&B albums released this year alone that intimate some sort of gloom, either through melancholic production or lyrics about loneliness and doing drugs to numb pain. Quality aside, a lot of these albums tread the waters of the human psyche without penetrating too far so as not to ruin the mystique. There’s no unraveling taking place; instead we’re presented with an image of jaded indifference to life that seems superficially cool from the outside. It’s not that this is somehow a lesser expression of anguish but it’s hard to get emotionally wrapped up in someone’s guarded hints at something deeper yet to be unfurled. It takes a lot for someone to be truly honest about their turmoil.

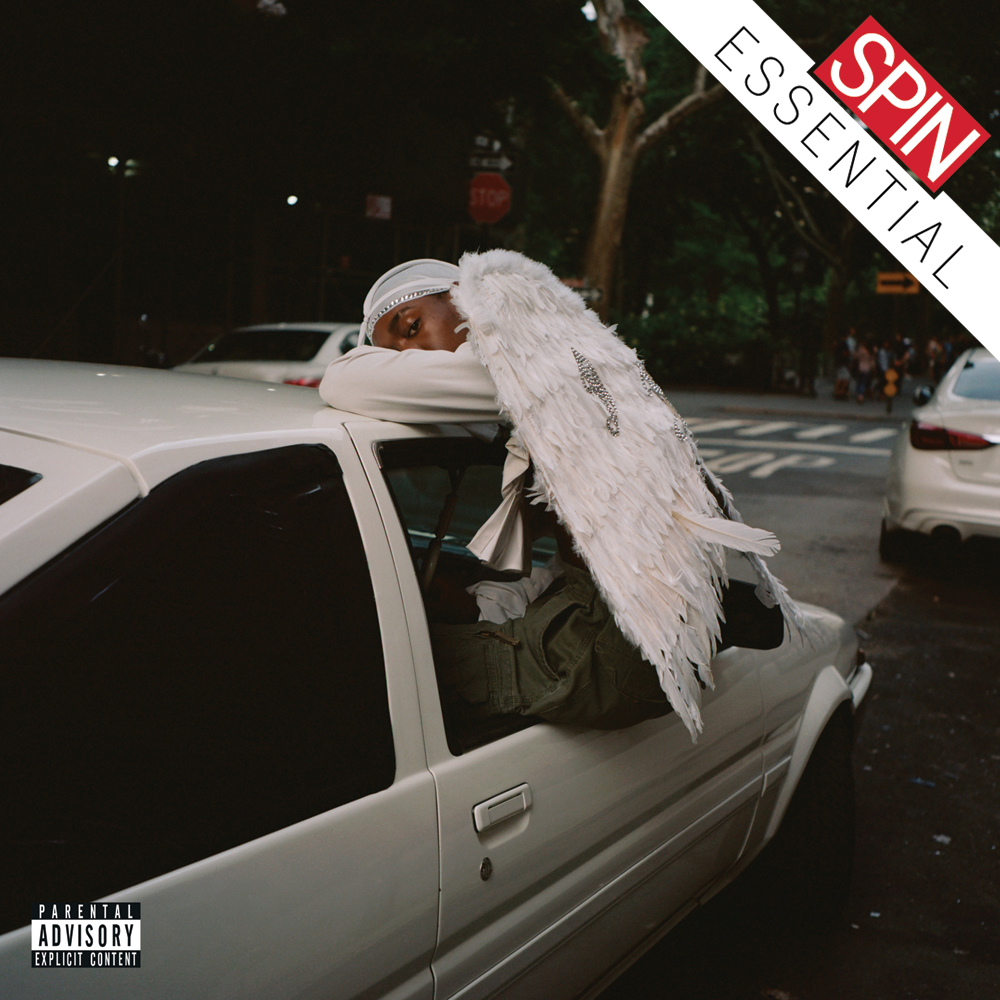

Negro Swan, the sixth album from Dev Hynes and his fourth as Blood Orange, takes depression and makes it personal, rendering it tactile instead of philosophical. Hynes impeccably orchestrates his jazzy art-funk, resulting in the best sounding music of his solo career. He uses these arrangements in order to tell us about the memories that still haunt him, the wretched thoughts that plague him, and the hope to which he still clings.

Part of Negro Swan’s power is in it’s specificity. The album’s opener, “Orlando,” tells the story of Hynes’ adolescence spent getting beat up by other kids, comparing the experience to something that should be magical: “First kiss was the floor,” he sings. The meld between something so violent with something intimate is effective in how it shows the ways in which the traumas of our lives poison can poison our innocence and tenderness. The warmth and softness of the instrumentation emphasizes the cloaking of horrors.

Negro Swan’s production is always pleasant at very turn, regardless of how grim it gets throughout. The album just sounds spectacular. Hynes’ penchant for half-formed, skeletal records that charm but leave you wanting isn’t really here. Instead, the tracks on Negro Swan are fleshed out, labored over, and canorous, with guitars, synths and elements of jazz providing warmth and space. Hynes and his collaborators’ voices are tools used to empower the arrangements of the music, like an added confectionary. Every track has the sensibility of a band jamming together during rehearsal, but in a way that sounds impeccably opulent. The album at once feels improvised and natural, but you can never see any sweat. When other performers show up, they serve specific purposes that bring out the best in each song.

Sonically, the album feels like a twin to a different Hynes-adjacent project: Solange Knowles’ musical tome on black angst 2016’s A Seat at the Table. (Hynes played a small role on that album but was much more instrumental in Knowles’ 2012 EP True.) Like A Seat at the Table, Negro Swan is wordy and weighty but extremely focused, a culmination of influences that have informed these artists over the years: their memories, poetic musings, conversations, complex frustrations and desires, the books of Maya Angelou, James Baldwin, or Alice Walker, and the music of Miles Davis, Aretha Franklin, Shirley Caesar, and Pimp C. All of the pieces that are soaked to make up a person are emanated on both records.

Here, instead of monologues from Tina Knowles or Master P, we get them from Janet Mock and, briefly, Puff Daddy. Mock’s interludes don’t care the same obviousness that A Seat At The Table’s did but you get the point nonetheless: it’s all about a recognition of a shared type of strife. Another grand album with which Negro Swan shares DNA is Frank Ocean’s Blonde, an enigmatic creative force making a statement that perfect captures a feeling of melancholy. Both are sonically similar records, using wistful guitars and warped, malleable vocals to intimate both a pleasure and coldness depending on the moment. With Negro Swan, Hynes had the wherewithal to make his music bouncier, though no less potent.

In it’s best moments, Negro Swan unequivocally understands something so authentic and humane about depression and anxiety—it’s a spectrum. There are moments full of grief and heartbreak but just before you think the album might drown too far and never see the sun again, a light strikes through. On “Hope,” vocals from Tei Shi and Puff Daddy alternate together in a delicate dance between the sorrow of heartbreak and wistfulness of the memories of a finished relationship. “Bring hope when you come around, I still smile when you come around,” says Puff, the simplicity of his words mustering so much about the forging of interpersonal bonds, even when they end in unfavorable manner. “Apparitions of your love, have you seen them falling short?” Tei Shi sings, puncturing the gut. To some extent, love songs and breakup songs are both easy, but there’s something more difficult about the vulnerability it takes to admit that you have seen love but couldn’t hold onto through faults of your own.

Expressing those difficulties along with the constant existential crisis of being alive is threaded throughout Negro Swan. Pain is terrifying and can erode the soul, but it’s also normal—so normal that sometimes you barely notice it. But the moment you are aware of it, it can be suffocating, particularly when it comes to being a black person.

With that in mind, there’s something relieving about Hynes’ exasperation on “Charcoal Baby,” which is about that microscopic feeling of having to represent blackness in one direction and justify your worth in another. “No one wants to be the odd one out at times / No one wants to be the negro swan / Can you break sometimes?” sings Hynes in flustered, needing fashion, the point stinging with incredible accuracy if you can relate. It’s a lyric that could apply to how white people and non-black people of color might view a black person like a zoo exhibit, or to feelings of “otherness” among black people for any reason at all. Most of all it gets at how tiring the burden of “meaning” can be when you just want to live as a nobody—going about your day without having to think about anything but the world in front of you at that moment if for only that day. It’s not always an appropriate desire to have or confess when you grow up around wizened elders who remind you from the moment you can walk to “don’t forget that you’re black,” but it’s a truthful and natural feeling to think it might be nice to do so for just a second.

Still, Hynes isn’t running away from blackness. Despite the world’s antagonism towards black people, his music and career has always embraced it. But instead of the overt stands of his last album, 2016’s Freetown Sound, the pro-black sentiment on Negro Swan is mostly musical—rooted in black traditions of jazz, soul music, Memphis rap, and even gospel. On “Chewing Gum,” Hynes brings a tender ballad into the murky, pulverized lo-fi production of an old Three 6 Mafia record, which is heightened by the presence of Project Pat’s and slowed down raps. The song has both a nostalgic warmth to it but feels decidedly modern, with the beat feeling specially made for nighttime drives where you can feel the vibration of your car’s speakers.

On “Holy Will,” Hynes enlists singer Ian Isiah to interpolate The Clark Sisters’ “Center of Thy Will,” with the same passion of hotbox black churches, just with electric guitars emulating gospel organ pianos. The song feels like Sunday morning worship, but more than that it feels like salvation, which—whatever bad politics and problems remain inherent to Christianity—is the goal of praise and worship. It’s a left-field choice for a Blood Orange album, but one that feels perfect amid an album that swerves between the trauma that threatens to cause a person to spiral and the love that person hopes can save them.

https://youtube.com/watch?v=y2kg3I3biyM

In sports, what commonly happens when a star player first shows up to a team is that their ascent is full of growing pains, full of sputtering starts and stops with flashes of amazing feats. There may be no structure that resembles anything truly transcendent yet, but eventually the stars align and that player finally puts it all together to reach the potential they were believed to have. Dev Hynes’ career, as a solo artist, has proven him to be a great talent with glimmers of sublime wonder, but ultimately seemed to be better applied in songs for others. The Blood Orange concept of unfinished drafts as the actual final product is pretty punk and artistic, but it had left his solo albums a bit lacking. The songs on Negro Swan are very much Blood Orange records, still with that half-done aesthetic, but now the production and the songwriting have become fully realized and sharp enough that these songs leave a lasting mark instead of leaving you to beg for just a little more.

On Negro Swan’s closing track “Smoke,” Hynes makes a sanguine statement that works as a fitting personal statement. “Balance in my hair, I’m pretty as fuck” he sings, which is a hell of a credo to live by on its own. But it’s the song’s last refrain that says it all: “The sun comes in, my heart fulfills within.” Maybe it’s too neat of an ending for an album that expertly deals in such intricate ideas, but it’s less a declaration than it is just a wish. It’s reminiscent of another thing you become too familiar with growing up in the black church to deal with the pain life brings —Psalms 30:5. “Weeping may endure for a night, but joy comes in the morning.”