As a white guy in hip-hop–a once-marginalized demographic that is now bordering on omnipresent–Eminem has always been focused on earning respect from his peers and from an audience looking for reasons to shun his very existence. Sixteen years ago, he declared that “a plaque and platinum status is wack if I’m not the baddest.” Today, despite healthy record sales, the consensus is that he’s more like the worst—exactly the thing he said he didn’t want to become.

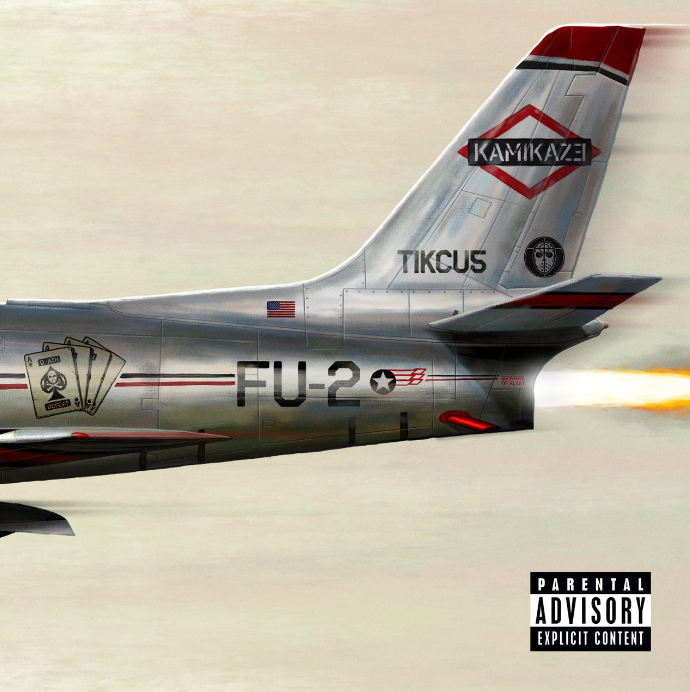

Eminem surprise-released his new album Kamikaze last week, seemingly intent on catching the world off-guard. He spends a significant chunk of his tenth album lashing out at people who didn’t like his ninth one, last year’s Revival, which sloppily augmented his multisyllabic verses with hooks and production that aimed for stadium-rock glory. When he’s not going after the critics, he sets his sights on younger, more currently stylish rappers. The album opens with “The Ringer”, a five-minute barrage against both parties. Over a gloomy beat, Em weaves in and out of couplets, mocking Lil Pump’s “Gucci Gang” and calling out Lil Xan, Lil Yachty, Machine Gun Kelly, and Iggy Azalea, though as a music critic he lacks incisiveness. He succeeded by sheer virtuosity and force of personality; maybe he’s angry that the aforementioned rappers don’t have to try as hard as he did.

In the social media era, when new leaders are crowned every day and cultural mores can change at a whim, the best-selling artist of the 2000s sounds hapless and adrift. (Does he know that Iggy isn’t even popular anymore?) It’s true that youth-focused cultures like hip-hop often frown upon elders who continue working past their prime. But Eminem’s defensiveness seems to preclude whatever reckoning he could otherwise have with any creative shortcomings that may have led him here. “Greatest” finds him hammering this point home with a superhuman flow and a hook about how he “woke up to honkies sounding like me.” The Mike Will Made It beat is nearly a soundalike itself, with a bassline that’s very similar to the low-register piano part from the producer’s work on Kendrick Lamar’s “Humble”—so much so that the final verse includes an homage to the song’s acapella “My left stroke just went viral” chant.

Also Read

WHEN EMINEM RULED THE WORLD

Eminem’s obnoxious teasing throughout Kamikaze makes it difficult to determine whether he’s simply annoyed or actually envious of today’s rap elite. Certainly, few of them can touch his technical ability. On “Lucky You,” he goes ballistic, with a master class in switching up cadences. But he wastes his talent on his obsession with the supposed faults of the current generation. Here, he’s asking “where the G Raps and Kanes at?” Later, “Not Alike” essentially devotes an entire song to explaining why he and Machine Gun Kelly have nothing in common, despite both being white rappers. (His beef with MGK goes back to 2012, when Kelly tweeted that Em’s then-16-year-old daughter was “hot as fuck.”) The song also slips in what could be construed as a jab at the Migos’, as the hook mocks the singsong simplicity of “Bad & Boujee”’s opening lines.

Putting his ego to the side if for just a moment, Eminem uses “Stepping Stone” to remind listers of the introspection that characterized career highlights like The Marshall Mathers LP. The song is a cathartic tell-all about the dissolution of his friends and onetime Shady Records signees D-12 after the death of the group’s leader Proof, though Em’s heartfelt need for closure runs the risk of being received as trite. “Nice Guy” and its successor “Good Guy” are equally earnest, but further expose a glaring flaw that’s long tainted Em’s catalog: verbal abuse and threats of domestic violence. At this point, these lyrics not only indicate lack of growth—in the wake of society’s recent grievances against misogynistic famous men, they practically beg for attention and controversy. But the world has moved on. Even Tyler, the Creator, the most obvious descendent of Eminem’s shock-and-awe style, has since changed his approach. On “Fall,” Em calls Tyler a “faggot.” He censors the word with a bleep, but not its intent. Tyler has not responded.

Marshall Mathers has long used music to shed light on his childhood trauma, and it stands to reason that Kamikaze is the result of some still-unresolved sensitivity. There’s also hypocrisy at work in his outbursts at critics, coming from an artist who once marketed himself by making fun of everyone, from handicapped icons to boy bands. His skill is still intact, but his music lacks its former inspiration, and he only digs a deeper hole for himself by taking aim at the youth. If he truly wants to be left alone, maybe he should just ride off into the sunset and leave the thin-skinned antagonism to someone else.