Mary Lou Lord’s interview with Elliott Smith was originally published in the April 1998 issue of Spin. On the occasion of our list of the best alt-rock songs of 1998, we’re republishing it here.

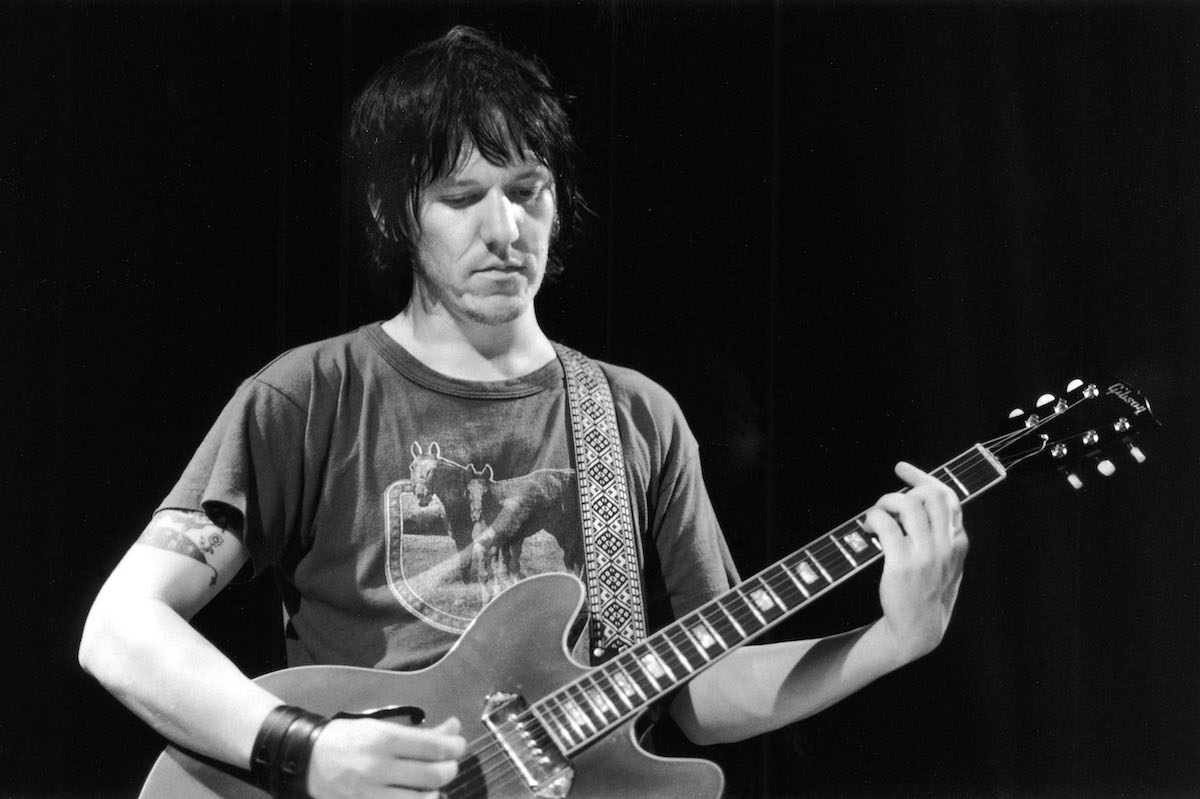

Musical compatriots Mary Lou Lord and Elliott Smith have seen each other at their greasiest—the morning after a gig in some college town, sipping Styrofoam-flavored coffee and loading the van for the next stop on the indie-rock two-lane. Throughout the ’90s, the pair wrote, recorded, and toured together, two singer/songwriters able to quickly hush rooms full of long-haired flannel-flyers. Now, they’re both on the road to bigger things: Lord has just released her major-label debut, Got No Shadow, while Smith’s songs are prominently featured, at director Gus Van Sant’s personal behest, in the recent film Good Will Hunting. Fame looming, the two nevertheless set aside time recently for some cigarettes and soul-searching.

Mary Lou Lord: Whenever I hear you talk about songwriting you don’t usually refer to “the song that I wrote.” You usually say “the song I made up.” Why is that?

Elliott Smith: I don’t know. I guess it’s a more natural way for me to say it. “I wrote it” makes it seem like I sat down and figured it out. It’s more like something that sort of pops into your head. It’s a little attempt to deflate the process.

Your songs seem so offhandedly beautiful; they remind me of songs I loved growing up. Is there any kind of corny stuff that you liked when you were a kid?

You mean, like, skeletons in my closet?

You know: the Carpenters, Burt Bacharach, “This Guy’s in Love With You.”

Oh, sure! I’m always happy to bring those out. That stuff is practically all I ever listen to anymore, songs that have something about them that would be really cool if you could extricate them from their ridiculous situations. For example, you don’t have to be into the super-sappy words, but you might like the cool wah-wah guitar solo on Bread’s “Guitar Man.” But whatever one person thinks is ridiculous may not be to somebody else, and you can take it out of that ridiculous situation and put it into your own ridiculous situation. Which I plan to do.

I saw you a while back with your band, and you would bust into that line from the the Association’s “Never My Love.”

I think it’s a great song.

It’s beautiful.

I mean, some of the words, they’re not words I could make up. I don’t know if they’re words I’d really want to sing. But it’s such a beautiful song. It’s got really cool chords. And I always liked parts of songs that are the turnaround, where it changes key and stuff.

“Say Yes” [on Good Will Hunting] is a great example of that It has a gorgeous turnaround in the bridge. That song sits right up there with “Never My Love.” The Beatles’ “Something” is another one. I have a big place in my heart for those types of songs-1 always wonder, “How did somebody come up with that?” Do you ever surprise yourself when you write?

If I don’t, then I don’t like the song. I mean, I don’t surprise myself like, “Whoa, that was brilliant,” I never think that. But I surprise myself like, “Huh!?” Like with “Say Yes,” I wrote that song in five minutes. And I wrote “Between the Bars” [also on Good Will Hunting] right after that. Both of those I made up during an episode of Xena: Warrior Princess with the sound off, which is a great way to write songs. Your eyes are busy, so they don’t get bored and they don’t watch what your hands are doing, so then you can surprise yourself. Your hands can surprise you with things they know and that you don’t.

I think that some of the best songwriters have also been people who have mastered the craft of listening. Maybe that’s one of the reasons you can write—you can just listen forever and when you need a reference, it’s in you. It just amazes me that there are these people who get hits on the radio and you sit there and you talk music with them and they have no idea what you’re talking about. I think, “God, how did they get this far?”

Still, I know very well that my songs have no place on the radio. It’s not because radio is a bunch of crap—it’s just that radio doesn’t play my kind of stuff. And I can’t dress up my songs so that they’ll fit on the radio, because they wouldn’t be the same songs anymore—whereas your songs would be, you know? It’s a kind of talent that you have that I don’t.

I wouldn’t want to change to fit any kind of format, but there are a few changes that made on the new record—compromises, maybe—with the production. Because I do want the songs to get the fairest shake they can. And if it has to sound a particular way to get on the radio, we’ve done that. It’s like a beauty pageant. And the only way that I could get in is if I wore a blue bathing suit. [Laughter] And it wasn’t much effort to say, “All right, instead of the purple one I’ll wear the blue one.”

But, like, I can’t wear the blue bathing suit, because I’m already wearing a red bathing suit! And whether or not anybody wants to see me in a red bathing suit, I’m gonna wear it. [Laughter] Because for me, the sound of the song is the same thing as the song itself, you know? Both ways are cool, totally—I think it’s great to have the flexibility to do what you did in production. But when I make up stuff, I can’t imagine it in a lot of different settings.

Here’s a question I get asked a lot: What would you say makes an acoustic song a folk song?

People seem to think that everything that’s played on the acoustic guitar is a folk song, which is insane. It’s a stylistic thing. Folk is distinguished from pop by almost always having a moral to the story, a point. Whereas pop songs often don’t really have any point—or they have multiple points, and none of them are especially clear. Both styles are obviously good, but for me, I like pop. It’s more vague, there’s more possibilities in it.

But people are always comparing you to the folkies of yore. Nick Drake is a big one. Bob Dylan. But I think you’re more like Joni Mitchell. Do you listen to Joni?

Well [Laughs], I mean, I’ve heard Joni Mitchell before. But, like, I don’t sound anything like her.

That’s not what I’m saying. It’s more in the same way that girls latched onto Joni Mitchell, these kids really latch onto you. it’s that self-confessional thing—it’s just so sweet and beautiful. So not cynical. You know, a lot of people might say that your songs are sad—and, in a way, yeah, they are kinda sad. But for me they’re like a vaccine against sadness—you have to take some in order to take it away.

They make me feel better, too. But then, if I were to look at the words, and pretend I’m not me, I would have to go, “Yes, this is pretty depressing.”

It’s kind of wild that you’ve become this acoustic heartthrob, don’t you think?

A what?

A heartthrob.

Um, I don’t feel like a heartthrob.

C’mon, the last time you played in New York there were tons of Hollywood types there.

I guess. I mean, I don’t know who comes to see me play. The lights are pointed in the wrong direction and you can’t see people unless they’re right in front. And after the show’s over I go right back to my hideout.

Tell me it wasn’t fun going to the big Good Will Hunting premieres.

Yeah, they were pretty fun. I had fun at the one in New York because I wore my white suit with a big pink flower. I always seem to have fun when I wear that suit.